Can 12 million fish be wrong? Virtually no finned critters were to be found in the San Dieguito Lagoon as recently as 2007, when bulldozers began to push tons of earth to create berms along the banks of the coastal waterway. Seven months later, in January 2008, marine biologists were astonished to find millions of baby fish – far in excess of their expectations – squiggling in the newly irrigated lagoon in San Diego County.

Birds also showed up. During a three-year period starting in 2006, when the first phase of the environmental restoration began, waterfowl species nearly doubled in number from 89 to 160. "Clearly, there was an unmet demand for habitat," said Kelly Sarber, a biology consultant who serves as spokesperson for the $90 million effort.

On paper, the 150-acre San Dieguito wetlands restoration project, which is scheduled to reach completion this fall, seems fairly straightforward: Newly constructed river banks, or berms, along the lagoon and the San Dieguito River will channel ocean water into the wetlands. During severe floods, the new berms will prevent silt from overflowing the river banks and spoiling the habitat.

Downstream from the lagoon, biologists have replanted the barren flats with native plants that now thrive on the edge of newly filled saltwater ponds. The lagoon remains open to the ocean year-round, so the tidal action of the Pacific can recharge the water inland. Ms. Sarber singles out the work of Hany Elwany, the hydrologist who figured out the proper levels of tidal water needed to keep the wetlands alive, while controlling the flow.

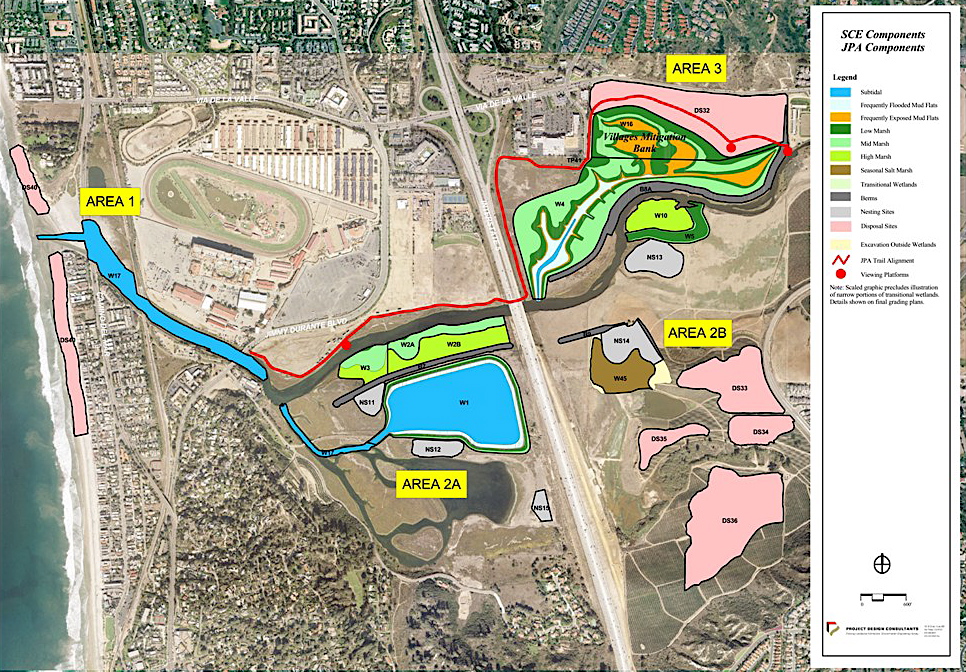

Components of the $90 million project, adjacent to Del Mar Fairgrounds, are seen here.

Coastal wetlands are also a suitable home for some famously endangered species, including the California least tern, the light footed clapper rail and the Belding savannah sparrow, and could stabilize the populations of the threatened birds over the long term. The same habitat, of course, is suitable for many other animals, including frogs, coyotes, raccoon, striped skunk, opossum, mice and rabbits, along with assorted reptiles and invertebrates that complete the bio-balance.

Heading the project are two power companies – Southern California Edison and Sempra Energy, the corporate parent of San Diego Gas & Electric – who took on the restoration of the San Dieguito marshlands. The project fulfills the power companies' obligation to mitigate the effects of hot water disgorged by the San Onofre nuclear power plant a few miles up the coast; water from the reactor kills many fish larvae. The power companies will maintain the wetlands until the year 2050, when responsibility for the marsh will go to a joint powers authority made up of surrounding cities.

The speedy response of wildlife may have been particularly gratifying for the biologists, hydrologists and other experts who pursued the project for 16 years before obtaining the necessary entitlements from a host of public agencies, including the California Coastal Commission, the state Department of Fish and Game, the State Lands Commission, Caltrans, the cities of Del Mar and San Diego, the San Diego Regional Water Quality Control Board, the Army Corps of Engineers, the Coast Guard, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the 22nd District Agricultural Association. I have no problem with placing stumbling blocks in the path of developers and overweening homeowners who want to muck up the coastline. But why should wetlands restoration projects travel the same tortuous route?

The degradation of the San Dieguito wetlands followed a familiar story line: Early in the 20th century, the area was drained for farming. During the Second World War, the military built an air strip on the former coastal marsh. Later, in the 1950s, Interstate 5 installed a concrete wall down the center of the wetlands. The rapid growth of San Diego County, meanwhile, hemmed in the wetlands on all sides, endangering the wetlands themselves.

Local support for wetlands restoration has been strong and organized, however. After 75 acres of wetlands were restored during the mid-1980s, local residents pushed for further restoration of 150 acres. The San Dieguito wetlands project becomes part of a 440-acre wetlands, providing the scale and "critical mass" that biologists say is necessary for a viable habitat.

An artist's renderings of the project once it is completed.

As it says in the Talmud, one good deed begets another. In this case, the wetlands are a centerpiece of a larger ambition to create a greenbelt that stretches from the ocean to Volcan Mountain, 55 miles away. In 1989, the joint powers authority—made up of the city and county of San Diego, plus the cities of Del Mar, Escondido, Poway and Solana Beach—acquired 20,000 acres of land in the area. Another 20,000 acres are already under public ownership. Currently, about eight miles of the "coast to crest" trail exist, and proponents say they hope to complete the corridor within 10 years.

The San Dieguito project has not been free of political hiccups (see CP&DR Environment Watch, September 2003). Last August, the City of Del Mar briefly went into a tizzy when a draft land use proposal for the wetlands suggested designating the entire city and its popular beachfront as a protected area. City officials feared such designation would prevent Del Mar from replenishing the sand on its beachfront. The proposal did not move forward, and Del Mar's beaches actually benefit from the wetlands, because the sand that accumulates in the lagoon can be used to replenish the city's beaches.

Kerfuffles aside, the San Dieguito wetlands restoration has some historical ironies: Our forefathers were eager to drain the marshes in the 19th and 20th centuries, and California has lost 95% of its coastal wetlands. Today, we spend heavily to recreate those same wetlands, which have become prized open space amenities. By itself, the growing fish population vouches for the success of restored wetlands in San Diego County. Fish don't talk, of course, but they don't lie, either.