San Marcos is suffering from a syndrome. (We're talking metaphors here, gentlemen; no need to call the process server.) The name of the ailment that afflicts this attractive, upscale suburb north of San Diego could be called Nowhere in Particular Syndrome. The symptoms include the lack of a center, coupled with a sense that one could be nearly anywhere in America—anywhere, in fact, that suffers from the same anonymity.

The treatment, still experimental, is to graft a city center onto this bedroom community, much as one would transplant some genetically healthy tissue onto a diseased organ. If the cure takes, the city will not only gain a center, but the healthy DNA of this transplant might spread beneficially to other parts of the organism.

This "transplant" is the San Marcos Creek specific plan. In late July, the San Marcos City Council unanimously endorsed the plan, which calls for high-density commercial and residential development, together with new parks and open space, as well as some flood control measures. In addition to 90 acres of parks and open habitat space, the specific plan will allow 1.2 million square feet of retail space, nearly 600,000 square feet of office space and up to 2,300 housing units.

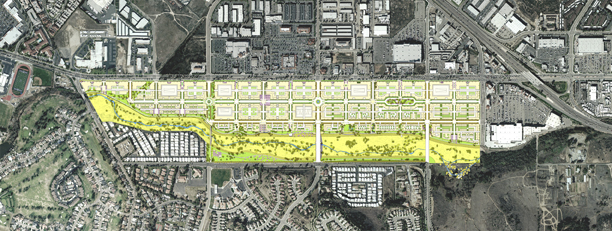

The 217 acres of the specific plan area encompass the creek's 100-year floodplain, and the idea of locating a new downtown in such a place sounds odd. Yet the creek bed and its surrounding floodplain lie in the center of town, bounded by four major roads, including State Highway 78. The creek is also a dividing line between the older, commercial part of the city on the north, with its familiar configuration of shopping centers floating in a lake of asphalt, and the newer, spaghetti-street residential neighborhoods to the south. In other words, the stream that has served as a natural division between the older and newer parts of town can now function as the place that connects the two.

The San Marcos Creek project would squeeze a new downtown between the commercial part of town (top) and residential neighborhoods (bottom).

The design of the specific plan area logically locates the commercial and high-density residential uses along San Marcos Boulevard, the northern boundary of the project area. The shapeless parking lots suddenly transition into smaller, pedestrian-oriented blocks that measure roughly 400 feet by 310 feet north of Main Street, and 400 feet by 280 feet south of Main. Those dimensions are a little larger than the blocks in downtown San Francisco, but it is still a walkable scale. To make the blocks even more accessible to pedestrians, the blocks are "to be further broken down through the provision of private paseos and alleys," according to urban designer Michael Olin of WRT/Solomon of San Francisco, the firm responsible for the master plan.

The parks and riparian habitat lie mostly south of the creek, bordering the existing residential neighborhoods, and the softer lines of the open space element of the specific plan are as carefully designed as the formal blocks to the north. During the public hearing process, the designers had shown a PowerPoint presentation of all the things that the San Marcos Creek specific plan was not supposed to be, including "a developer's wildest dream." That statement was not intended to say that the specific plan would be hostile or inimical to developers; the real meaning is that the plan would not be shaped entirely by commercial concerns, but instead by respect for the natural environment and the health of the waterway. The design decisions made by WRT/Solomon for the relationship between the open space and the areas to be developed demonstrate the designers' respect for both commercial viability and the life of the creek.

To appreciate this design, take into consideration an idea that an architect recently shared with me. To create the most usable open spaces, whether they are courtyards or parks, the open spaces should be designed first. After the footprints of the open spaces are determined, then design buildings around the open space. This simple principle, so commonsensical, is actually the opposite way we design most of our parks and habitats, which are leftovers that developers don't want, such as hilly areas or wetlands.

Taking a close look at the southern edge of the developed area in the San Marcos plan, we see that a newly designed street, Creekside Drive, mimics the meander of the waterway, maintaining a near-uniform depth of open space on either side of the creek, whichever way the waterway happens to turn.

Notice, also, how the blocks of development yield to the path of the water and the surrounding riparian environment, as if the creek had eroded the streets. This primacy given to open space, and the way that commercial development yields to the requirements of a healthy creek, demonstrates the good faith of the specific plan, and proves that it is not guided by the rapacity of developers. My hope is that the rhythm of walkable blocks will someday spread north into the formless retail district and spread the DNA of walkable streets farther into San Marcos.

Flood control takes the form of new levies on both the north and south of the creek, particularly near a mobile home park, which currently is vulnerable in the event of a flood. A new culvert beneath Highway 78 would drain the area if the creek rises.

High densities and a mix of uses would provide the San Diego suburb with a real downtown.

According to local news reports, the only San Marcos residents who spoke out against this plan are people who are concerned about high-density development, which is fair. They were also concerned that the new downtown San Marcos might become a regional attraction, which seems less of a real issue, because there are plenty of other places for the residents of San Diego County to shop. Downtown San Marcos will probably remain mostly a local attraction.

As one of millions of Californians who live near lifeless, channelized waterways that could have been wonderful places, given a different history, I eat my metaphorical heart in envy for the good fortune of San Marcos. But envy is a different disease altogether.