I was studying the Beach and Edinger Corridors Specific Plan for Huntington Beach the other night. One of the chief goals of the specific plan is to remake Beach and Edinger into first-rate streets worthy of this Orange County community of 200,000 people, replacing the messy, strip-like conditions that currently exist on these major thoroughfares. With the deadline for my column looming, I fought to stay awake, but soon fell asleep.

With my feverish brain preoccupied with streets, it should have been no surprise that I dreamt of Baron Eugene-Georges de Haussmann, who during the 1860s designed � and ruthlessly pushed through � a set of magnificent boulevards in Paris, including the widening of the Champs Elysees. �

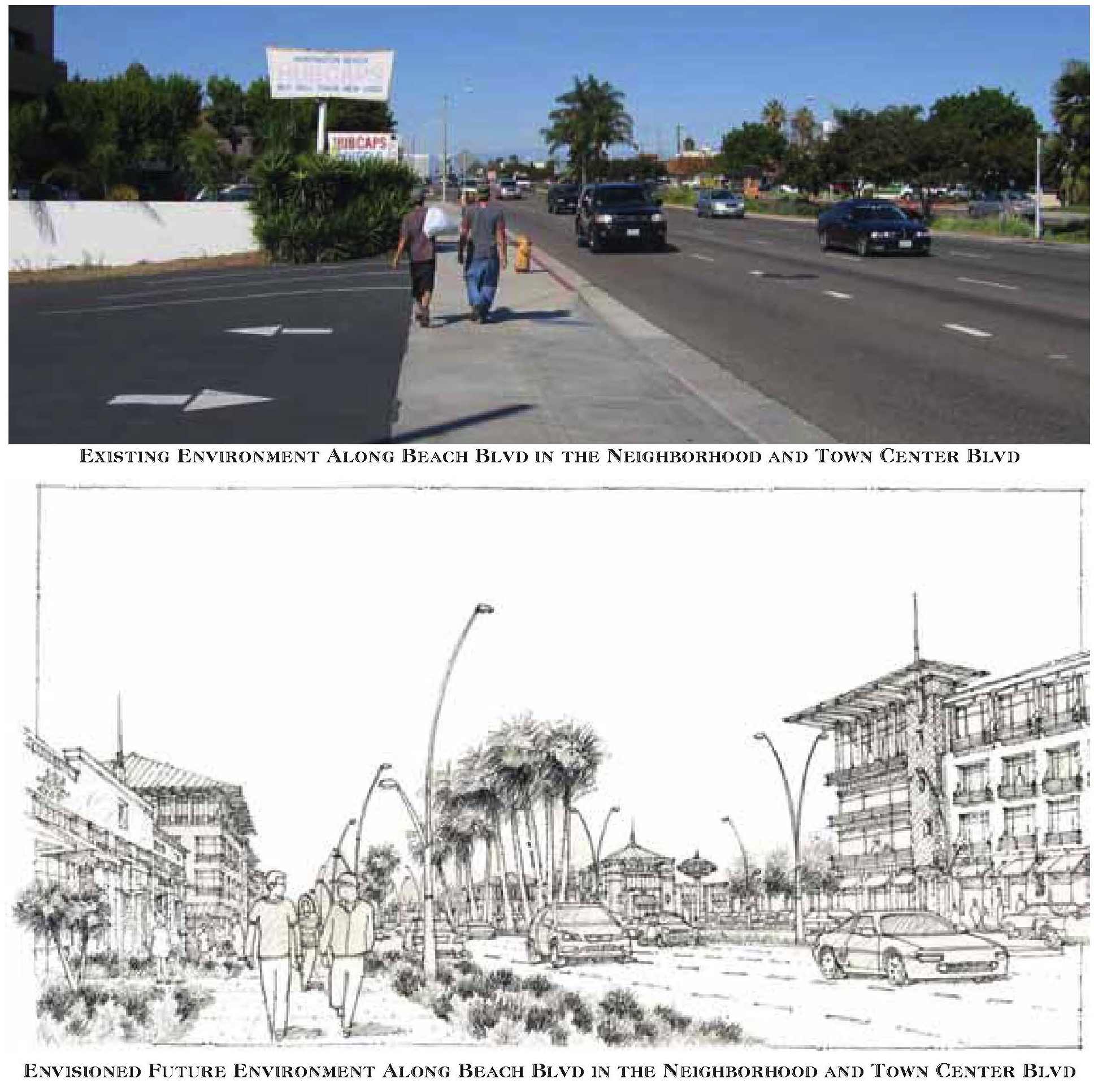

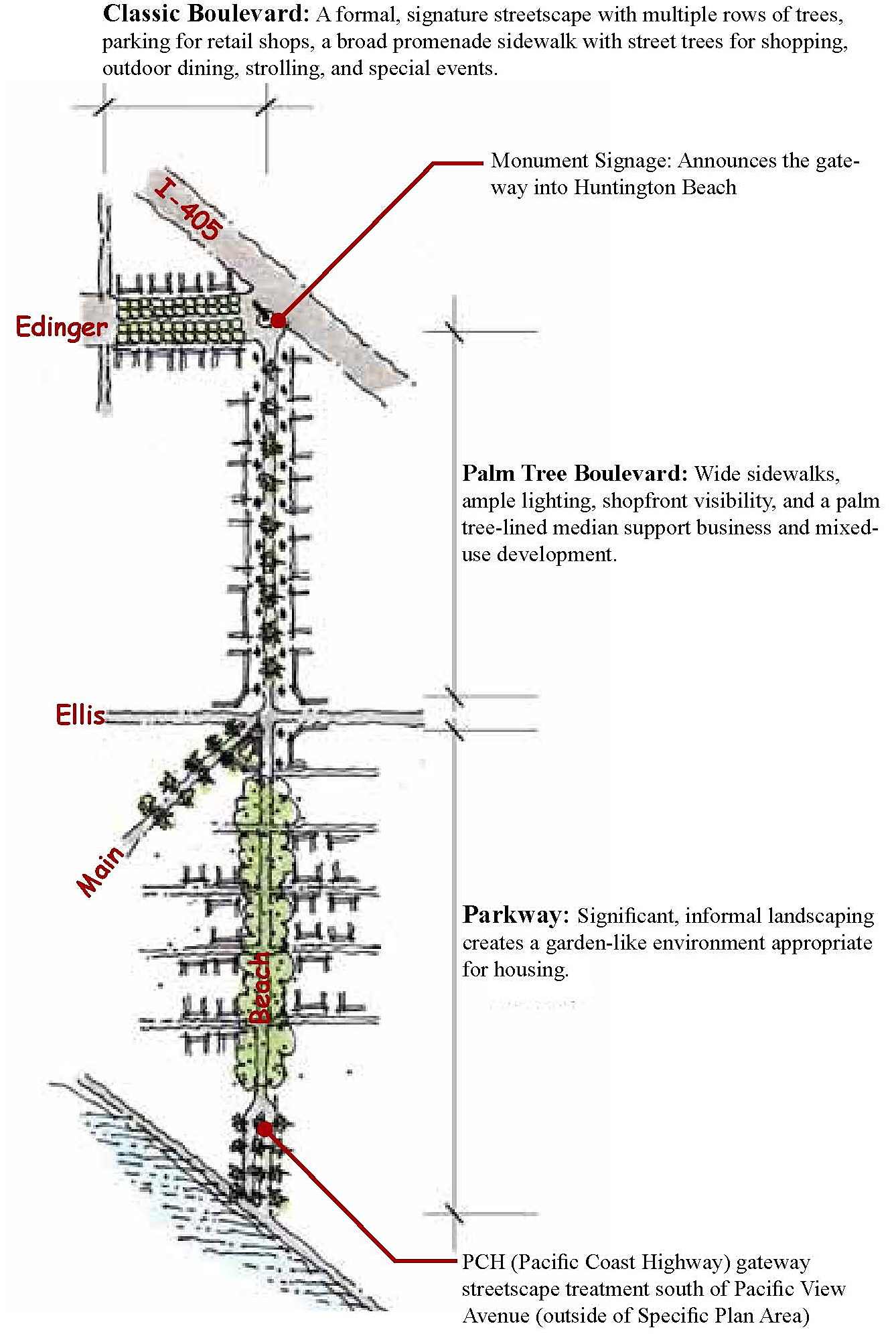

I quickly showed M. le Baron the specific plan document prepared by the urban design firm of� Freedman Tung and Bottomley. He was delighted with the crisp drawings of tree-lined streets, flanked on either side by buildings four and five stories tall, inspired in large part by his own grand, formal boulevards. Then his eye fell on something that caught his attention.

"What is this nonsense?" he thundered, as he pointed accusingly to a portion of text. "What does the gentleman mean exactly, when he says that the boulevard should be series of centers, with stretches of street in between serving as infill," he said with an almost palpable distaste.

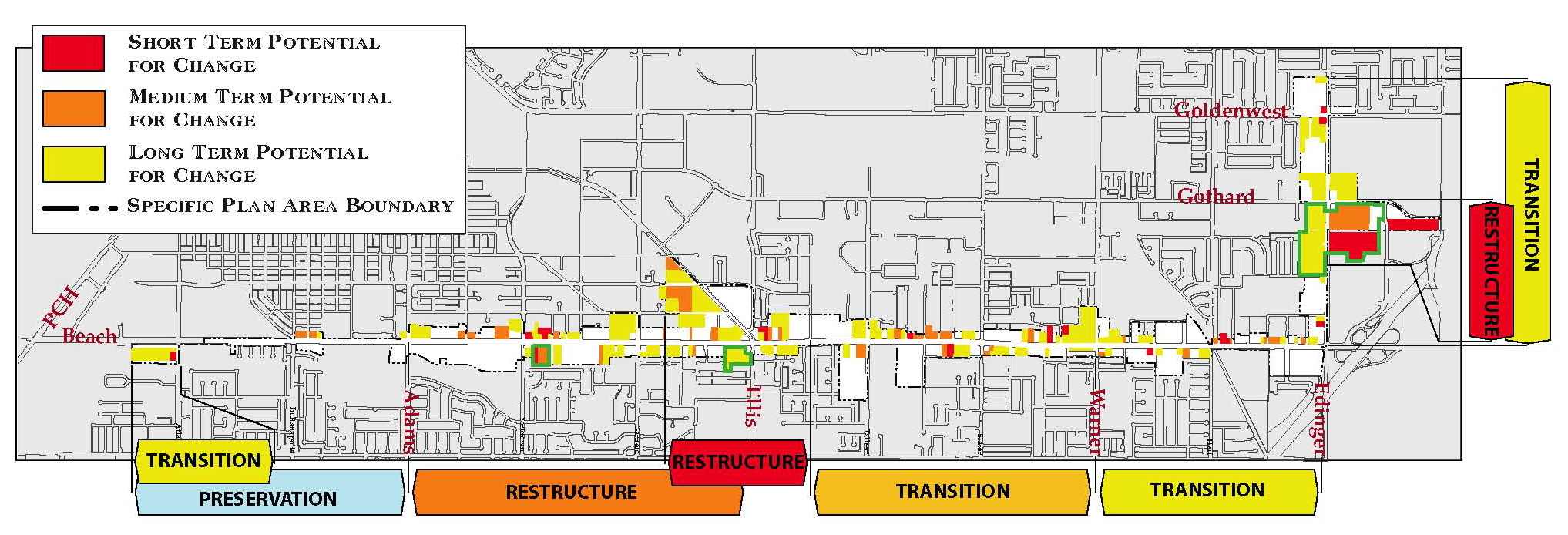

I tried to explain to this distinguished visitor that the city wants to develop the streets to their full commercial potential. The strategy, as outlined in the specific plan, is to use existing retail centers as "centers" that would be reinforced with new housing, and office and mixed-use buildings.

"Bah! Nonsense," said the Baron with 19th Century confidence. "Streets do not have centers. Cities have centers. Where streets converge, that's where you have a center, just as I arranged a dozen boulevards in Paris to converge on l'Arc de Triomphe."

I tried to explain to the Baron, so brilliant but so hopelessly out of date, that� this plan is essentially a democratic document. Real estate investors and merchants were clearly among the many voices that Huntington Beach heeded, and understandably so: City Hall clearly wants to boost sales tax and property tax revenue on these major streets, and that means promoting merchants. "Bah," said the Baron derisively. "Streets do not exist solely for the sake of merchants. Streets are for all the citizens."

I tried to explain to Monsieur le Baron that planning in 21st Century California often ends up as a complex arrangement among different groups, sometimes with very different agendas. Even a cursory look at the specific plan reveals a tension among contradictory goals. In one place, the city states a goal of creating beautiful streets that encourage people to walk. On the same page, we find an expression of support for more auto dealerships, a condition that pedestrians shun.

"Foolishness," said Baron Haussmann. "You can sell your cars somewhere else. A great street is no place for such uses."

Again, I tried to explain to the good Baron that the world had changed considerably since the time when Napoleon III had given Haussmann near-dictatorial powers over the capitol of the French Empire. "At the risk of offending you, M. le Baron, I think you do not fully appreciate what we're trying to do in Huntington Beach. In a democracy, we try to build a consensus toward a plan that satisfies all the different goals. Planners want a great boulevard, merchants want foot traffic and the city officials want sales tax revenue. The compromise solution is a first-rate shopping street with retail prominent among a mix of uses."

After listening patiently, the Baron growled. "I simply cannot understand why you Americans insist on doing things in an indirect way," said the Baron. "Rather than simply build the boulevard, you want to create a set of incentives and whatnot, with the hope that a great street will emerge, as if by lucky accident, through the promotion of shopping and other uses. It is sort of like trying to make a woman fall in love with you by standing on a street corner and playing the mandolin, hoping to attract her attention. It is not impossible, of course, but far from certain. You would be better off writing love letters, sending gifts by the hour and threatening to drown yourself in the Seine. That approach is much more direct."

"In addition," the Baron continued, "I am not convinced that this plan, despite excellent research and the best intentions, actually accomplishes what it sets out to do. Boulevards are characterized by continuity. Here, in your Huntington Beach, you are proposing some new development around this shopping center and that one, hoping that the in-between places will fill in somehow. If you were to take this type of planning to its logical extreme, you would end up with something very similar to that infernal place, the Las Vegas strip, where you have giant clumps of development � the casino hotels � separated from one another by long stretches of parking lots or T-shirt shops. Is that the kind of multi-center street you want?"

At this point, I confess, I grew impatient. "My dear Baron, I must protest. Not all of us have the emperor of France as a client. We live in a democracy, and planning must reflect the goals of all the people."

"Or those who have the most money and speak the loudest," replied the Baron, with a directness bordering on rudeness. "Democracy may be a good political system � nay, the best possible � but as for planning, give me autocracy any day. Vive l'Empereur!"

At that point, the Baron vanished, and I awoke to the sound of a jackhammer breaking up concrete on the site of a new car dealership. And I still hadn't made up my mind about the specific plan in Huntington Beach.