Impermanence? What's that? Don't planners, architects and developers make stuff that lasts forever, or at least for a very long time? The technocrats of city making are not interested in empty lots and other temporary conditions per se. Empty lots have no value in themselves; they are only blank canvases for their grandes projets.

Plus, empty lots are short-lived – unless, of course, you are living through the worst recession in a half century, and every development project in California is standing as if flash frozen in July 2007, when an arctic blast from Wall Street withered the housing market and all of real estate finance.

Empty lots, it turns out, can be interesting and even useful, especially during economic down times. In San Francisco, a number of architects and landscape designers have created temporary uses for cleared construction sites or abandoned construction pits. Finding a temporary use for empty lots discourages graffiti and other kinds of vandalism, which are indicators of places that are socially dead and up for grabs. More to the point, temporary parks or exhibitions can replace eyesores with spaces that give pleasure and in some cases prompt us to think and talk to other people (the phenomenon William H. Whyte called "triangulation").

Last spring, John King, the estimable architectural writer for the San Francisco Chronicle, invited local designers to submit ideas to reuse some conspicuously vacant spaces in the city. Unlike in many design "competitions," King did not hand out awards or commissions, and the request for empty lot redesigns was reality based. If projects are ever to be built, they will likely rely heavily on volunteer labor and donated materials. Those constraints actually made the empty-lot competition more interesting than a blue-skies type of contest. A tight budget demands simplicity, and simplicity tends to result in strong design solutions.

Ned Kahn, a local artist, contemplated filling a construction site at Fifth and Mission with steel cables on which small metal discs are strung like beads. The discs move easily in the wind, allowing viewers to visualize the movement of the wind. (The piece is not entirely dissimilar from a public art installation by the same artist at San Francisco International Airport.)

For a different site, in a high-rise district of Crescent Heights, is a proposal called People's Public Workshop, which would be a group of exhibits explaining the tools and materials of urban infrastructure. The proponents are an imaginative local design collaborative called REBAR, whose practice seems to combine elements of both architecture and performance art.

REBAR deserves extra credit for popularizing the idea of devising new uses for ugly or under-used city spaces. The firm's greatest notoriety comes from inventing the annual event known as PARK(ing), in which different participants commandeer streetside parking spaces and make individual stalls into mini-parks. The idea seems precious and off-putting until we realize that a little bit of green (such as temporary sod lain on the street) and some shade actually make the street feel very different than before.

For a different site, this time on Rincon Hill, a team composed of Berkeley-based PWP Landscape Design and Kennerly Architecture & Planning propose an unconventional construction fence, with individual fence poles topped by bird houses designed for particular species, while an on-site construction crane would become overgrown in vines—a lovely Gothic touch.

For a different site, this time on Rincon Hill, a team composed of Berkeley-based PWP Landscape Design and Kennerly Architecture & Planning propose an unconventional construction fence, with individual fence poles topped by bird houses designed for particular species, while an on-site construction crane would become overgrown in vines—a lovely Gothic touch.

Octavia Boulevard, where the City of San Francisco owns at least 12 vacant lots, is an ideal showcase for temporary installations. In this case, the city's Office of Economic Development has been considering different short-term uses for its properties.

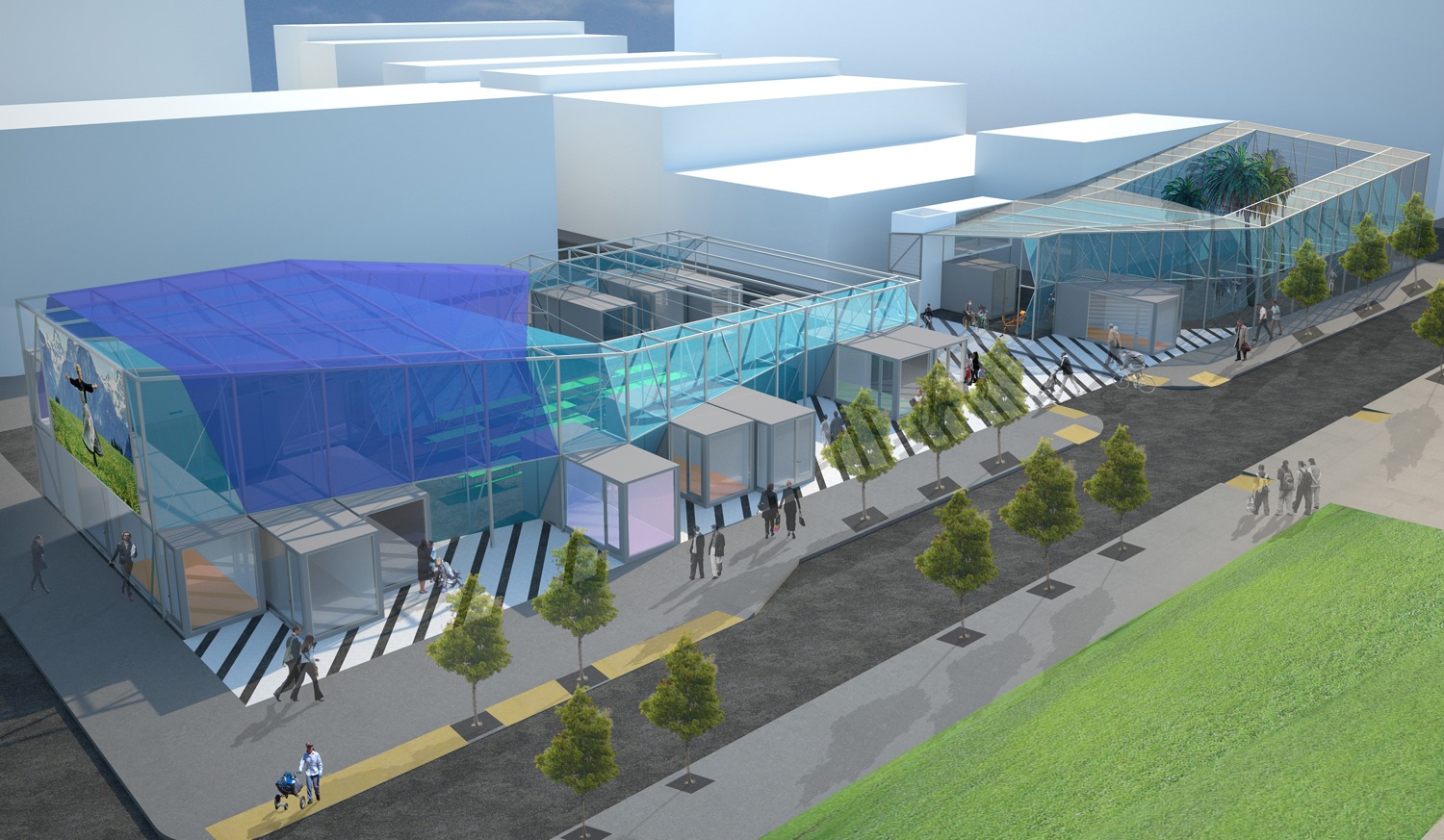

One proposal for Octavia is a multi-use structure called PROXY, designed by Oakland based architect Douglas Burnham of Envelope A+D. Covering two empty parcels at Octavia and Fell Street in front of Hayes Green, PROXY is not much more complicated structurally than a refreshment stand at a county fair: Essentially, it's a group of 9-by-20 cubicles made from off-the-shelf scaffolding and draped in tensile fabric. Inside these elegant, if minimal, spaces are a food court, shops, an art gallery and an outdoor movie screen. Above all, PROXY would offer a place with seating and shade. The proposal is as practical as it is extravagant.

One proposal for Octavia is a multi-use structure called PROXY, designed by Oakland based architect Douglas Burnham of Envelope A+D. Covering two empty parcels at Octavia and Fell Street in front of Hayes Green, PROXY is not much more complicated structurally than a refreshment stand at a county fair: Essentially, it's a group of 9-by-20 cubicles made from off-the-shelf scaffolding and draped in tensile fabric. Inside these elegant, if minimal, spaces are a food court, shops, an art gallery and an outdoor movie screen. Above all, PROXY would offer a place with seating and shade. The proposal is as practical as it is extravagant. For a different parcel on the same street, a nonprofit known as MyFarm proposes a "communal farm." The group raises produce in the backyards of 120 homes in the city, and the Octavia proposal seems like an extension of the idea of eking farmland out of urban sites.

For me, the big light bulb in all these proposals is the recognition of the potential flexibility in urban land use, in contrast with the narrow and single-purpose way we usually make design decisions. Construction sites or underused lots may be either forbidding no man's lands or serve as vibrant public spaces.

Sometimes temporary uses have a way of lasting longer than originally expected. Nearly a decade ago, I wrote a piece for Landscape Architecture magazine about a temporary garden planted in a site immediately west of Los Angeles City Hall, where a federal courthouse is to be built. For whatever reason, the courthouse is still in the future, and the low-maintenance garden of tall, native grasses continues to flourish.

A few blocks away, on Grand Avenue, is another temporary solution: an ugly steel parking structure that locals call "the tinker toy," which has stood in the same site for more than 40 years – longer than the life of some commercial buildings. Nowadays, the tinker toy rises across the street from Frank Gehry's Disney Hall, where it provides a constant note of ugliness within sight of the finest recent building in Los Angeles. Temporary can be a very long time, indeed.

What if a garden or an exhibit hall replaced the tinker toy, at least for the time being? Public gardens are a solution that gore no oxen while providing something positive to urban life. And because cities are never finished and always in transition, there's a permanent need for the artfully temporary.