Tom Bradley's dream for downtown Los Angeles was never realized – at least not in the form he originally envisioned. The city's biggest-thinking mayor (1973-1993) of the postwar era, Bradley wanted a great downtown like those in Chicago, Houston and San Francisco. By the 1970s, L.A.'s period of greatness, as distinct from mere bigness, had started: Los Angeles had surpassed Chicago as the nation's second largest metropolis, while the Los Angeles and Long Beach ports, clogged with imports from booming Asian economies, were now busier than the New York-New Jersey ports. Los Angeles was the American gateway to the rising tigers of Asia, just as New York was the American gateway to a declining Europe.

Los Angeles needed a downtown commensurate with its new status as financial hub of the West Coast. This downtown would have soaring towers, silk ties and firm handshakes. This downtown would be an essential location for Corporate America and all the blue stockinged lawyers, accountants and consultants holding its train. Above all, downtown would impose a center on a notoriously uncentered city, as if to rebut H.L. Mencken's notorious snark that Los Angeles was no more than a "group of suburbs in search of a metropolis."

Today, downtown L.A. has become a great residential neighborhood and a significant office market, although developers and market forces ultimately played a bigger role than government or public policy.  Prior to the 1970s, L.A.'s faded and obsolete downtown was fit for a smaller city of an earlier era. The center of downtown was the iconic City Hall on Main Street, a white tower with battened walls and a pyramidal dome that for many years was the tallest building downtown by city ordinance. Completing the symbolic triumvirate of downtown power was St. Vibiana's Cathedral, the seat of the Archdiocese for a heavily Catholic community, and the Los Angeles Times building. Industry and warehouses centered on the rail yards on the east side, near the river. The office district stood in the terra cotta covered buildings of Broadway and Spring Street, while Seventh Street's cluster of department stores was the regional shopping destination. The Pacific Electric Red Car made downtown a principal hub of a four-county commuter rail network. The rest of downtown was housing, primarily frame houses, some of which had fallen into slum-like dilapidation. Novelist Christopher Isherwood famously decried Bunker Hill as "the most squalid" neighborhood in the country.

Prior to the 1970s, L.A.'s faded and obsolete downtown was fit for a smaller city of an earlier era. The center of downtown was the iconic City Hall on Main Street, a white tower with battened walls and a pyramidal dome that for many years was the tallest building downtown by city ordinance. Completing the symbolic triumvirate of downtown power was St. Vibiana's Cathedral, the seat of the Archdiocese for a heavily Catholic community, and the Los Angeles Times building. Industry and warehouses centered on the rail yards on the east side, near the river. The office district stood in the terra cotta covered buildings of Broadway and Spring Street, while Seventh Street's cluster of department stores was the regional shopping destination. The Pacific Electric Red Car made downtown a principal hub of a four-county commuter rail network. The rest of downtown was housing, primarily frame houses, some of which had fallen into slum-like dilapidation. Novelist Christopher Isherwood famously decried Bunker Hill as "the most squalid" neighborhood in the country.

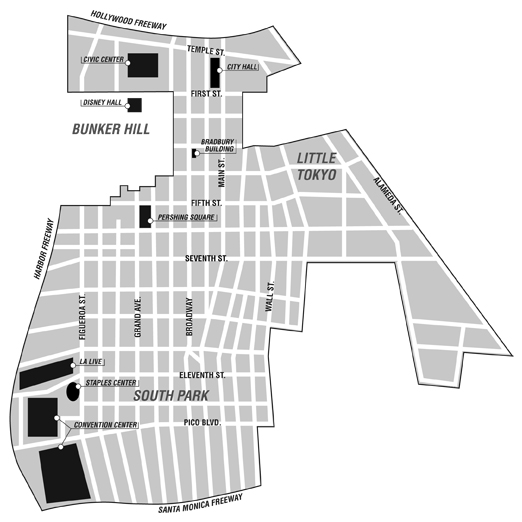

Highway construction during the 1950s and 1960s gave downtown new, de facto boundaries, with Interstate 10 to the south, Interstate 110 to the west, and the junction of Highway 101 and Interstate 5 on the north. On the east, the channelized Los Angeles River provided a fourth concrete boundary. The freeways "isolated downtown from the rest of town," according to Carol Schatz, president of the Central City Association, a trade group that promotes relocation and business growth. The former city center had become an island of bureaucracy. While industrially vibrant, downtown was rarely visited by the middle-class residents of the Westside or the San Fernando Valley. Downtown wasn't "nice." Unless you were a bureaucrat, a juror or a builder pulling a permit, there was no reason to go there.

The Central Business District

To achieve his downtown vision, Bradley realized the Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA) was his most important ally. Through seven different redevelopment project areas, the agency virtually carpeted the whole of downtown. Other city agencies, however. seemed to resent a redevelopment agency that danced to its own tune, while catapulting its chosen developers over the snake pit of the city's notorious entitlement bureaucracy. Detractors complained the CRA operated almost as a government unto itself.

The powerful City Council in this weak-mayor city also seemed both wary and envious of the redevelopment agency. Councilmembers routinely waved through projects with little discussion, yet the council on several occasions tried to rein in the powerful agency and yank redevelopment, and its money, away from an ambitious mayor. The most lasting damage occurred in 1977 with the settlement of an oddball lawsuit brought personally by Councilman Ernani Bernardi against the agency. His suit charged that the redevelopment agency aided the development of office buildings at the expense of low-income housing and other social services. (Advocates of redevelopment might argue that the agency needs big taxpayers to finance affordable housing.) To settle the suit, the agency agreed to cap the spending of tax increment revenues in the Central Business District at $750 million. Repeated attempts to renegotiate the cap during subsequent decades – Bradley later suggested $5 billion – went nowhere because the settlement precluded any changes without all parties' agreement.

The First Super Project: Bunker Hill

After its formation in 1949, the CRA soon seized upon Bunker Hill as "Redevelopment Project Number One." For the next two decades, the agency commissioned a series of master plans in which large commercial buildings would replace declining residential neighborhoods. Following the scrape-and-rebuild mode of classic urban renewal, the agency demolished all the housing in 1970. In 1979, the agency finally settled on a master plan for an 11.5-acre area that called for an extremely dense project of 11 million square feet of office space, 3,000 apartments and 2,000 hotel rooms. The agency sought out developers, and the two finalists were a Chicago firm affiliated with Metropolitan Life Insurance Company and Rob Maguire II, a then-unknown who had assembled a team of young architects, including Cesar Pelli, Frank Gehry and Barton Myers. The agency chose Metropolitan Structures, perhaps for its financial strength, although its bland design of three identical, reflective glass towers, each 1 million square feet in size, seemed anti-climactic, even sadly ironic, after decades of planning.

The CRA was forward thinking, though, requiring developers to build public amenities in exchange for public subsidies such as land assemblage or the sale of land at below-market rates. The agency, however, often played a weak hand in negotiating the devil's bargain of asking private developers to build public amenities. During the early 1980s, the CRA negotiated with the California Plaza developers to build the new Museum of Contemporary Art on that commercial campus. For some reason, the agency accepted a design that located the museum's front door 20 feet below street level. (My guess is that Metropolitan Structures did not want the cultural building to block the view of a hotel and apartment complex from the street.) The resulting museum building looks as if the ground had slumped beneath it, leaving only the pointed roofs visible from Grand Avenue. Renowned architect Arata Isozaki reportedly quit the job at least twice before its completion in 1984.

Even more questionable was the design of a regional shopping mall in Citicorp Tower. Although the agency had long desired fancy shopping downtown, the CRA allowed the developers of the three-tower complex to sink a new shopping center into a hole 50 feet below street level. Except for a decorative "space frame" above the hole, the shopping center was invisible from the street. The developers apparently did not want the shopping space to block the view of their office towers, and the idea of designing the two together somehow did not occur to them. This bizarre underground mall, made up of three descending rings of retail centered on a shadowy round courtyard, resembled something out of Dante's inferno, except it was cold. The unfortunate center remains open today.

If new public buildings were questionable, office buildings were hot. In 1985, foreign investment punctuated by the $550 million purchase of the Arco Plaza office complex made downtown L.A. arguably the most desirable place for a West Coast developer to buy or build. Even though some suburban office markets commanded higher rents than downtown, overseas investors targeted the center city, perhaps in belief that the center city would contain L.A.'s most valuable office market. By the 1990s, a real estate brokerage could publish a map of downtown office buildings with foreign flags attached to most of them.

Despite record prices for land and buildings, downtown was not penciling out. Downtown's Fortune 500 companies, never great in number, almost disappeared entirely due largely to the late 1980s' merger-and-acquisition activity. Arco, IBM, Unocal and Security Pacific Bank all departed, leaving acres of empty sublease space that spoiled the market for full-price "landlord space." Downtown office buildings were rarely more than 85% occupied, the break-even point for many landlords.

Macroeconomic troubles followed. The S&L meltdown combined with the Japanese banking crisis halted new office construction. Shuwa Investments, which had been Southern California's leading Japanese investor, was exposed as a naked emperor, having built its real estate empire by borrowing against the paper value of its stock market holdings. When those holdings went poof, the once-mighty investor vaporized like smoke from an incense burner. Since 1992, no speculative office project has been built downtown, although developers continue to propose them and the city has actually approved several.

A New Wave Of Public Investment

During the subsequent lull of the 1990s, the CRA continued to invest heavily in downtown L.A. The agency doubled the size of the convention center, while developing new apartment buildings and residential complexes in Chinatown, Little Tokyo and South Park, an area of aging industrial buildings and parking lots that the agency wanted to transform into a residential neighborhood. The agency built two apartment buildings and a condo complex in South Park, but market-rate housing was a tough sell. Except for people commuting between the U.S. and Asia and downtown business owners, few wanted to live downtown. By the late 1990s, downtown's 2,000 residents remained almost invisible amid the transient population of 500,000 daytime workers.

Downtown also seemed resistant to the idea of loft housing, despite the popularity among artists of converted concrete buildings in the industrial area. Obsolete building codes didn't help; the small number of developers attempting to convert older buildings in the office district found they needed special variances. Even when completed, these pioneering developments sometimes fared poorly, because they were often isolated from other residential buildings. Developer Ira Yellin, who pioneered private sector preservation in downtown L.A. with the refurbishments of the sky-lit Bradley Building, Grand Central Market and Los Angeles Union Station, lost money during the early 1990s when he converted the upper stories of the Million Dollar Theater, an ornate movie palace, into rental units.

Yet room to grow was limited. Architect Chris Martin told the Downtown News during the late 1990s that many aging office buildings were obsolete and impossible to convert to modern office space. Without a viable option for reuse, he warned, many buildings faced demolition. Downtown L.A. was choking on its own history.

A single city law resolved this crisis and changed the urban landscape. In 1999, the City Council approved the adaptive reuse ordinance, a law sponsored by the Central City Association that encouraged developers to convert old buildings to housing by relaxing certain building and safety requirements.

Historic buildings line Broadway.

One outspoken developer was Tom Gilmore, who converted three 19th Century office buildings into what he called the Old Bank District. In the great Los Angeles tradition, Gilmore was a tireless promoter who stumped for downtown living from every platform he could scramble onto. His great discovery was rehabilitation of several adjacent buildings at one time, creating a sense of both community and safety. While some renters would complain of alleged shortcomings in his rehab efforts, Gilmore had done the impossible: He had popularized downtown loft living in Los Angeles, albeit after other large downtowns had long since hopped on the rehab wagons of SoHo, SoMa and LoDo. Los Angeles, in fact, was "the last major city to embrace downtown loft conversions," said Schatz, of the Central City Association.

Developers and their lenders are herd animals, risk averse and hesitant to explore. With the acceptance of the Old Bank District, however, local and national developers were soon building luxury condos in older buildings, while new residential structures arose on former hamburger stands and parking lots. The one-time Standard Oil headquarters became The Standard, a hip hotel with a marquee stylishly hung upside down. (If you had to ask why, you were too hopeless to stay there.) Formerly feared and shunned by young professionals, downtown soon filled with the fleshpots of the yuppie and dink classes. Adaptive reuse and gentrification had achieved where urban renewal had failed. By the time Bernardi's curse came true in 2000 and the central district ran out of redevelopment money, it seemed a non-event. Downtown's loft scene had the "big mo." By 2008, nearly 47,000 people lived inside the freeway ring, according to the Central City Association. "I don't know exactly which number represents critical mass," said Schatz, "but I think we have achieved it."

The Next Super Projects: Grand Avenue And LA Live

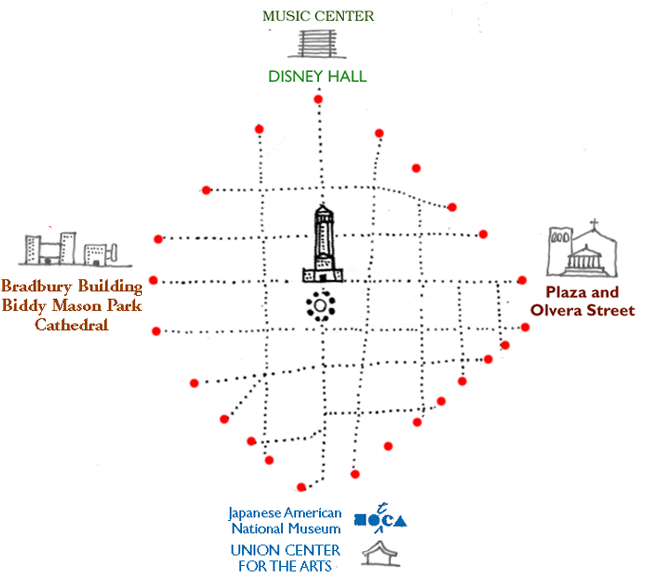

When the Frank Gehry-design Disney Hall opened in 2004 after two decades of management and design changes, cost overruns and fundraising, downtown finally had a swashbuckling masterpiece for what had become an arts corridor. The concert hall, the new Los Angeles Cathedral, The Colburn School of music, the Museum of Contemporary Art and the Los Angeles Music Center, a Lincoln Center knockoff dating from the 1960s, all stood along a three-block stretch of Grand Avenue. The CRA thus shifted into high gear to create the "connective tissue," such as townhouses and single-story retail buildings, to tie all the buildings together. The CRA commissioned urban architect Doug Suisman to develop ideas about public space. He proposed a grassy median running down the center of the boulevard, inspired by Barcelona's ramblas, if much narrower.

The development potential of Grand Avenue lay in four large land parcels on the steep slope directly east of the street; half of those lots were owned by the City of Los Angeles, the other half by Los Angeles County. The city and the county, which typically clashed over downtown development, in this case created a joint venture to develop the lots in a single super project. Part of their motivation was a longstanding ambition to grow rich by selling surplus land for commercial development.

Grand Avenue, however, was an odd design problem. The construction of Bunker Hill's enormous office buildings had required the removal of nearly all the underlying soil to make room for parking structures and access roads. The hill was gone and all that remained was a street, really a bridge, spanning a freeway entrance.

Ironically, the CRA, which had invented Bunker Hill in its modern form, found itself muscled aside in the Grand Avenue design competition. In the wake of the Bernardi lawsuit, the agency had no money to hand out, and, hence, little influence. The agency was forced to stand aside while a "public committee" of city and county officials, led by firebrand Supervisor Gloria Molina, reviewed the proposals. Managing both the "public process" and the expectations of the elected officials were two experienced hands, developer Jim Thomas and insurance magnate Eli Broad. The competition came down to two nationally known developers, both of whom proposed high-rise towers for apartments, condominiums and hotel rooms. Eventually, the officials chose The Related Cos.

The company had just completed the well-regarded Two Columbus Circle in Manhattan, a pair of twin towers designed with three floors of retail immediately above street level. Molina, a champion of low-income housing, signed off when the developers set aside 25% of the units for that purpose. Related's proposal appeared similar, including plentiful retail, to its New York towers. But even with the prestigious Gehry as urban designer, the extremely dense high-rise scheme relegated Grand Avenue to the status of foyer for a 500,000-square-foot shopping experience. The five-tower project serves the investor demand for high-rise "product" to the near-exclusion of all other types of housing, shoehorning an East Coast project onto a Los Angeles site. Because of financing problems, development has fallen more than two years behind schedule.

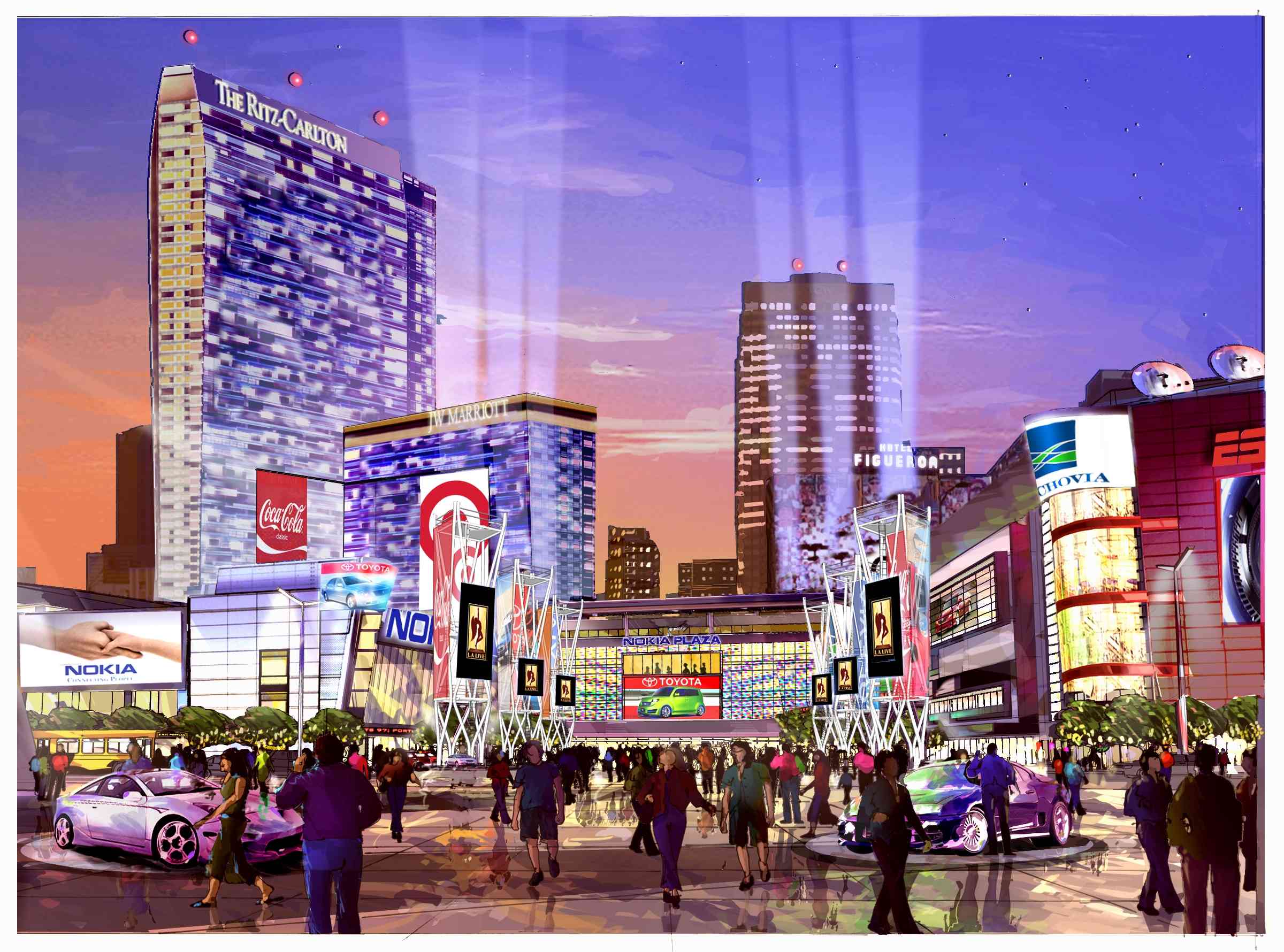

The third Super Project is LA Live, an entertainment and hotel extravaganza nearing completion on the southern edge of downtown, near the convention center. The city has long wanted a convention center hotel, which it considered the missing ingredient needed to book national meetings. Built around the existing Staples Center sports arena, this 17-acre project includes the Nokia Theater, nightclubs and a 53-story tower containing two separate hotels and 200 high-priced condominiums, stacked atop one another like layers in a parfait dessert. Jumbotron images animate a central courtyard.

The commercial bombast of LA Live

In a further show of impotence, the CRA applauded the project while allowing its long-nurtured South Park project to get steamrolled. The attainment of a convention center hotel is the fig leaf that allows the agency to pretend that at least one of its original priorities survives within this $3 billion act of usurpation. Developer Philip Anschutz was able to build this self-contained, inward-looking, anti-urban monument to his sports, theater and ticket-sales empires simply by filing an amendment to the city's general plan. So much for 30 years of planning. A billionaire developer with an alluring project will inevitably have his way with the city, in every sense.

It is hard to mention planning in this context without bitter irony. The cash-poor, politically orphaned redevelopment agency – formerly the downtown agenda-setter – now must rubber stamp whatever the City Council wants. Otherwise, it is hard to imagine how an agency with an avowed mission of "quality urban design" could encourage a giant project that disregards the rest of downtown, to the extent of setting up an opaque wall on Figueroa Boulevard.

The considerable flaws of Grand Avenue and LA Live, however, do nut nullify the larger achievement of downtown Los Angeles. If Tom Bradley's downtown of economic domination was never fully realized, something better arose in its stead: A pedestrian oriented urban neighborhood where the selling points are human-scaled urbanism, plus the regional attractions of a large job market, mass transit, education, culture and entertainment.

Above all, downtown is convenient, especially if you leave the car at home. "We walk everywhere – to the movies, to the supermarket," said a 30-year-old woman of my acquaintance, who shares a child-free apartment with her husband. When you tire of Super Projects, you can take a walk through the restored Union Station, a masterpiece of Art Moderne dating from 1940 and downtown's finest building prior to Disney Hall. Across the street is Philippe's French Dip restaurant, where a cup of coffee costs 10 cents, just as it did 40 years ago. You can explore the produce and flower markets during the early morning, and buy a decent suit for wholesale in the Garment District. As imperfection goes, it's not bad.