Los Angeles' housing crisis has been building for long enough that just about anyone who rents an apartment here could have told you about it years ago. But it wasn't until last summer that UCLA released a report confirming what many of us already know: as a function of average rents (high) and average incomes (low, especially compared to those in San Francisco and New York) Los Angeles is the least-affordable rental market in the country.

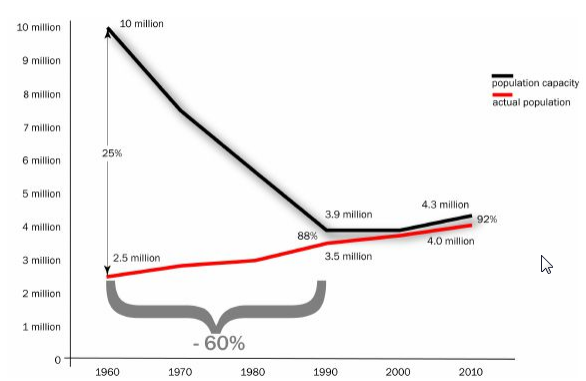

Circulating around the blogosphere now is a single graph that illustrates why:

This graph comes from a dissertation by UCLA Ph.D. student Greg Morrow, posted on the blog of Prof. Richard Green, of USC. Green showed it to me on Friday at the Urban Land Institute's Urban Marketplace conference. I'd like to say that we had a lively discussion (which we did, on other topics) so much as we shared a moment of mutual speechless bewilderment. The graph mostly speaks for itself: Los Angeles' population is, after 100 or so years of development, just about equal with the city's maximum allowable population.

As Henry Grabar puts it in Salon, Los Angeles has "reached capacity."

What this means for housing costs is obvious: the difference between those two lines is affordability. It's also opportunity for developers. Constrained supply and ever increasing demand equals insane housing prices. In a typical industry, supply would never become this constrained. Firms would produce more, or consumers would seek substitutes. Equilibrium would be restored. But this is real estate, and those rules don't apply.

Usually "constrained" is used as a passive verb, as if it's something that just happens. But the "hand" here is very much visible. When we think of "capacity," Los Angeles didn't lose 60 percent of its landmass en route from 10 million to 4 million, and it didn't lose 60 percent of its water, power, food, or sewage capacity either (though the first one remains to be seen).

Those 6 million men, women, and children were zoned, voted, and legislated off the island.

That downward slope tells a fascinating tale for anyone who's not currently struggling to make rent. The greatest irony is that Los Angeles' peak population of 10 million was allowed a time when its population was a fraction of what it was today. Either the city's public officials were thinking big prior to 1960, or they figured that even a number like 4 million was unthinkable, so what difference did a few more million make?

What happened, though, was a revolt by homeowners. The 1960s were heady times for the conversion of single-family homes into multifamily dingbat apartments, leading residents to fret about the loss of "neighborhood character." This usually equates with a fear of poor people and/or minorities. They were, at the same time, horrible times for public transit, as the trolly system clanged its last bell. The freeways ran smoothly for a while, but then they filled up, leading to more fears about growth.

Los Angeles has always been, a "reluctant metropolis," to borrow CP&DR publisher Bill Fulton's phrase, and the dream of the single-family home has held sway. Worries about the "Manhattanization" have persisted for years, never mind that even at 10 million people, Los Angeles would be about as dense as New York City as a whole, but still nowhere near as dense as Manhattan.

So, homeowners pushed through anti-growth legislation, advocated by residents who wanted to keep Los Angeles all to themselves. As Grabar catalogs in his Salon piece, small measures to keep Manhattan out of California included silly, unjustifiable requirements like setbacks, which do nothing but waste land, and parking requirements, which also waste land and jack up developers' costs.

On the more monumental scale, these sentiments culminated in 1986's Prop U.

Prop U, which is where that top graph bottoms out, was the mother of all slow-growth measures, down-zoning much of of the city's commercial areas. (According to its framers, Prop U itself was crafted not to directly impact housing supply.) It passed by a 2:1 ratio. What you can bet is that the actual sentiments among Los Angeles residents were probably flipped. Except, owners of single-family homes control 80 percent of L.A.'s residential land while representing a far smaller proportion of the population, so do they dominate elections. A 2013 poll by the Pat Brown institute found that "older voters and homeowners are disproportionately represented in mayoral voting."

Half-measures and creeping protectionism that had satisfied anti-growth activists during the 1960s and 1970s were no longer enough once they saw the city hitting 3.5 million. (Not coincidentally, the city's public transit system was in a world of hurt at the time, thus favoring lower densities and people who could afford cars and places to park them.) The implications of movements like Prop U were largely invisible for a while � you can't see what you can't build � until they started showing up in astronomical rents.

Today, many of Los Angeles' planners are trying to wring as much density out of the city as they possibly can. Developers are too. But, contrary to the stereotype of the marauding capitalist, they know as well as anyone that they build only at the pleasure of city policy and the public officials who can grant variances to it.

Los Angeles' planners are also working on ReCode:LA, a comprehensive, and much-needed, overhaul of the city's zoning code. You can bet that they're going to go for more density, especially around the city's new transit nodes. If the effort fails, though, that red line on the graph might one day overtake the black line. People are going to keep coming to L.A. whether the slow-growthers of 1986 like it or not. And we'll really have a crisis on our hands.

Reporter's note: This post has been updated to clarify the relationship between Prop U and residential zoning. Prop. U did not directly affect residential zones.