The development of affordable housing is inherently difficult. Projects typically require multiple funding sources, face neighborhood opposition, and are closely watched by both skeptics and state housing officials.

Yet California's need for additional affordable housing is undeniable, despite the crash in real estate prices. So CP&DR shares this look at three different projects to offer lessons for anyone involved in providing housing affordable to people of modest means: a crime-ridden, market-rate condominium complex that the Rialto Redevelopment Agency rehabilitated as affordable apartments; a new, eye-catching project in an industrial part of San Jose that serves 218 households making less than half of median income; and a project in Contra Costa County that overcame what appeared to be imminent failure.

Rialto Rehab

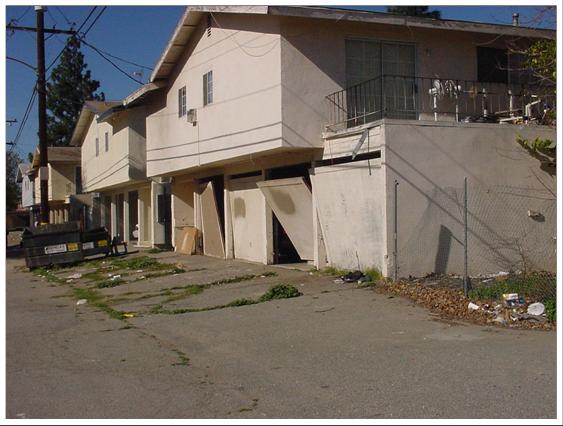

The Willow-Winchester condominiums were originally built during the late 1960s for first-time homebuyers. By the early 1990s, however, most of the 160 units had become rentals with absentee owners. Crime and drugs grew to be major problems, and the condo complex saw multiple homicides every year, said John Dutry, housing preservation specialist for the Rialto Redevelopment Agency.

"It was the worst crime area in Rialto. When we had calls for service, three police officers responded," Dutry recalled.

By 2004, the City Council had had enough and directed staff members to do whatever was necessary to solve the problem. The city's Housing Authority signed an agreement with the nonprofit National Community Renaissance (or National CORE) to revitalize Willow-Winchester, which would soon become Citrus Grove. At the time, about 120 of the 160 units were occupied, but only about 10 by condo owners. The Housing Authority began acquiring units quickly, as most owners were willing to sell. Acting as the Housing Authority board, the City Council approved use of eminent domain to acquire about a dozen units. All but two of the reluctant owners eventually settled and, by October 2005, the Housing Authority had control of all the units with National CORE as interim property manager.

The city then needed to empty the condo complex. The city evicted about 40 households because of nonpayment of rent or crime problems. The 10 owner-occupants were relocated, as were about seven renters. Everyone else vacated on their own terms, according to Dutry.

The Willow-Winchester condominiums (above) were revamped into the Citrus Grove project (below).

Construction started in the summer of 2006. Units were rehabilitated down to the studs, with the majority converted from two bedrooms and one bath, to three bedrooms and two baths. The city also demolished eight units to make space for a community learning center, which now houses a Head Start program, after school tutoring, day care, adult education and other services. Citrus Grove had its grand re-opening in October 2008.

"If you have the money and the will, you can make it happen. One of the secrets of the project was having the council 100% in support," said Dutry. He also credited National CORE for its expertise, as well the law firm of Stradling, Yocca, Carlson & Rauth for helping with rapid acquisition of units and the condemnation process.

The $37.6 million project had multiple funding sources: $7.8 million from the Proposition 48 housing bond, $8.2 million in tax credits, $14 million from the city redevelopment agency's affordable housing fund, $3 million from the HOME program, $2 million from the California Housing Finance Agency, and smaller contributions from other sources. Citrus Grove rents range from $351 to $864, depending on unit size and household income.

Rialto officials are now expanding the rehabilitation effort into a neighboring 42-unit complex that was slipping into the same crime trends as Willow-Winchester. The city has acquired the units and intends to start reconstruction later this year.

San Jose's Senter

In the last 20 years, San Jose has developed more affordable housing units than any other city in the state, and possibly the country. The city's Housing Department has provided about 16,000 units since it was carved out of the San Jose Redevelopment Agency in 1988. Paseo Senter at Coyote Creek is one of the newest projects. Completed last summer, the project provides 66 units for households with incomes no more than 25% of median, and 152 units for households with incomes no more than 45% of median.

But the project, said San Jose Housing Director Leslye Krutko, has done more than simply provide shelter. The project has features that provide services to Paseo Senter tenants and neighboring residents, she said. Child care is offered on-site in addition to a Native American community and health center, a swimming pool and tot lot, and facilities for kin caregivers, after-school programs and educational classes.

In addition, the project was designed to link two disconnected sections of Wool Creek Drive. The new extension provides vehicular and pedestrian access to an elementary school. Previously, students had to walk along very busy Senter Road and through an industrial park to reach the school, explained Ron Eddow, a senior development officer with the Housing Department. The project also involved a land swap that resulted in creation of public open space along Coyote Creek.

The site of Paseo Senter before the project (above) and after completion (below)

Architects at David Baker + Partners gave Paseo Senter a modern design with apartments that wrap around a parking garage, shielding the parking facility from view and providing tenants with parking on the same floor as their unit. The project's bright, tropical colors and central walkway (or paseo) provide an atmosphere far from the drabness of many low-cost housing projects.

The city worked with Charities Housing Development Corporation and CORE Affordable Housing to develop the $80 million project. Financing sources numbered 13, including $32 million in low-income housing tax credits, $18.5 million from the Department of Housing and Community Development's multi-family housing program, $12.9 million from the Redevelopment Agency's housing fund, $1 million from a state fund for support services, and $1 million from the Santa Clara County Housing Trust Fund.

"This is very special about the project. This is a lot of different funding sources coming into one project," said Alina Kwak, an analyst with the Housing Department.

More than 3,000 people, including many Vietnamese families who already lived in the area, applied to live in Paseo Senter. Rents start at $260 a month, compared with an area median of about $1,500.

Bay Point Rescue

When the Contra Costa County Redevelopment Agency completed the 52-unit Bella Monte apartment complex in the fall of 2005, it was cause for celebration. Located on a former junk yard near Pittsburg in the poor, unincorporated community of Bay Point, Bella Monte was intended to bring decent housing and a measure of stability to a rough neighborhood.

The California Redevelopment Association named the North Broadway Neighborhood Revitalization Program – which includes the Bella Monte, 69 market-rate houses and infrastructure improvements – the winner of a 2007 award for community revitalization.

But things were going wrong. In less than a year's time, nearly half of Bella Monte's tenants moved out, most voluntarily. It was beginning to look like even an award-winning redevelopment project could not survive in Bay Point. The Redevelopment Agency was willing to do physical improvements to increase Bella Monte security, but they were not going to improve the situation.

"The driver of our problem was a bar that was located across the street, and that had been both a code enforcement and law enforcement problem for many years," explained Jim Kennedy, the redevelopment agency's executive director. "It was bringing into the area a cast of characters that was spilling into the adjacent housing project."

What the county and the Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control found, according to Kennedy, was that the owners of Grover's Bar were elderly people who seemed unaware that their establishment had become a haven for prostitution, drug-dealing and minors seeking easy access to booze. Facing stepped up enforcement, Grover's Bar closed in early 2008.

The bar's closure, plus a few Bella Monte property management improvements, have made all the difference, Kennedy said. The lesson is that ongoing management – which is easily overlooked – is probably the most important part of affordable housing development, he said.