Westwood Village sits in the middle of a rare constellation of commercial districts. To the east lie Prada, Spago and the extravagance of Beverly Hills. To the south, Century City offers a resplendent new multiplex and every imaginable upscale chain store. To the west, Santa Monica's Promenade ranks as the paragon of L.A. urbanism. Further afield, the ersatz streets of The Grove and CityWalk attract "destination" shoppers from all over the region.

By the unusual standards of West Los Angeles, Westwood Village could be cited for blight. Yet even as other pockets of the Westside become ever more upscale, the city's new focus on "elegant density" and strategic infill might leave Westwood behind.

Westwood Village � an extraordinary jumble of short streets, odd angles, mixed use, and Spanish revival architecture next to UCLA � has for the past 20 years wheezed between two lives, neither Berkeley nor Beverly Hills. Today, a genteel tug-of-war continues between density and seclusion, youth and wealth, complacency and vibrancy.

"The demographics of Westwood Village are outstanding," said Laura Lake, co-president of Save Westwood Village. "It's strange that it's become the Bermuda Triangle of retail. But the potential is tremendous."

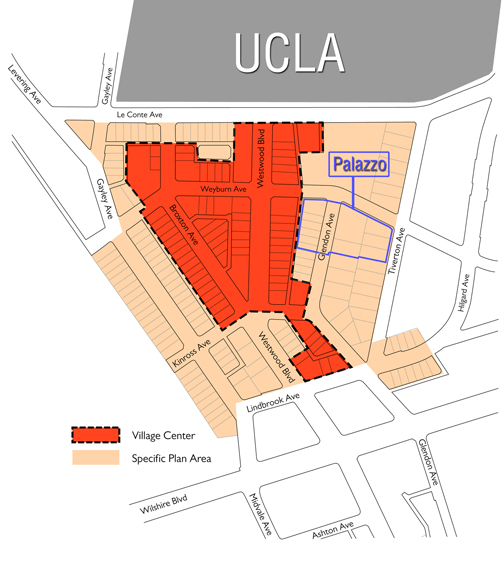

The latest and biggest attempt to realize Westwood's potential opened last month in the form of the Palazzo, a neo-Tuscan complex of 350 apartments, 1,200 parking spaces, and several storefronts. Its original design, critics say, tried to shoehorn nearly all of Florence into a city block. Countless meetings, revisions, and reinterpretations of zoning laws later, the Palazzo is now welcoming residents who, it is hoped, will stimulate the businesses outside their front doors.

"It is overly dense but may bring more life to the Village by having a residential population," said Lake. "The use was never the issue, but rather, the scale."

Rounding out what passes for a building boom in an area unaccustomed to new construction, a smaller mixed-use project, Plaza Lorena, is under

The Palazzo is the largest new project in Westwood Village in many years.

way just south of the Palazzo. Both developments hearken to a vision of smart growth and density that L.A. public officials, most notably Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, have been promoting.

City Councilmember Jack Weiss, who represents Westwood, said he welcomes "green, sustainable projects that encourage pedestrians and support transit." City Hall has not, however, put forward a cohesive strategy for the Village to promote growth � smart or otherwise � despite the Village's ready-made streetscape. The city, in fact, still relies on a prescriptive, 19-year-old specific plan for Westwood that encourages cars and discourages restaurants and bars.

The Palazzo's more discerning neighbors may yet decide whether a trend is afoot.

"I don't think there is such thing as �elegant density,'" said Sandy Brown, president of the Westwood-Holmby Homeowners Association. "The infrastructure in Westwood Village will not accommodate that kind of excessive development."

But the Palazzo is not merely big. Billed as a "catalyst for the Village," it combats blight with bling. With two-bedrooms starting at $3,700 and amenities that include concierge service and Pilates, few Palazzo residents are likely to be students. The high-end housing continues a trend, as UCLA Student Body President Gabe Rose said that condominium conversions have been eating up cheaper apartments and pushing the Village away from its buoyant past.

"I have this feeling that Westwood is becoming less of a college town," said Rose.

Old urbanism

Conceived during the 1920s as a commercial center for the university, the Village occupies a trapezoidal plot between Wilshire Boulevard and UCLA. Movie palaces and some of the city's best shopping attracted such large pedestrian throngs that by the 1960s cars were often banned.

"The bones are great," said UCLA Planning Professor Don Shoup. "A lot of what the new urbanists are recommending is what Westwood Village had from the beginning: a variety of densities, a village at the center, an interesting street layout."

"It's not new urbanism�it's old urbanism," said architect Stefanos Polyzoides, who co-founded the Congress for New Urbanism and designed Plaza Lorena.

But with history comes baggage.

By the mid-1980s the Village's weekend crowds had grown increasingly large, diverse, and unruly. Bloods and Crips shared uneasy streets with Bruins until an undiscerning bullet struck 27-year-old graphic artist Karen Toshima on a January evening in 1988. Almost overnight, crowds receded and Westwood became a forlorn enclave serving a local clientele.

"We hit rock-bottom," said Lake. "The merchants got hurt badly."

Toshima's story is cited so often it is easy to imagine that her ghost has been stifling Westwood. Lake said that to this day "residents don't want it so vibrant that gangs come in and problems happen." But, beyond the shock, more prosaic forces may have been undermining Westwood Village.

"I don't think that any of the problems that occurred in the past are what's keeping it from being successful today," said Paul Geigner, president of Topa Management, which manages 200,000 square feet of retail in the Village. "Those were anomalies."

Though its streetscape may be the stuff of Jane Jacobs's dreams, other aspects of the Village belong to planners' nightmares: chaotic parking, geographic constraints, the Westside's infamous traffic, and many stakeholders unconcerned about economic development. With Bel Air to the north and corporate offices to the south, there are few places in the world where the interests of freshman and tycoon are so entangled.

"One of Westwood Village's great strengths is the diversity of individuals, homeowners, students, merchants, and property owners," said Weiss. "This strength also presents challenges because each group � has a different vision."

The closest thing the Village has to a consensus is embodied in the Village specific plan, which represents the hopes, fears, and planning strategies of a bygone era.

Adopted, in a gruesome concurrence, on the one-year anniversary of Toshima's murder, the plan's stated goals include historic preservation, a "balanced mix" of businesses, and mitigation of impacts on local residential areas. Amended once, in 1991, the plan imagines a contrived reality in which particular stores serve just the right patrons.

In particular, the plan promotes retail at the expense of eateries. It allows no more than one fast food restaurant per 400 feet of street front, and conventional restaurants are limited to one per 200 feet � notwithstanding the fact that Westwood's appetite rivals those of many cities' downtowns. The plan also forbids stand-alone bars, and it puts upscale fast food in the same category as McDonald's. The plan does nothing to ease the Village's chaotic parking scheme, which requires redevelopment to provide a net gain of parking spaces amid a patchwork of private lots and 50-cents-per-hour street parking.

Though Lake called it "a visionary plan, particularly because of its incentives for historic preservation," it has presided over a commercial district that "has been kind of standing still while everything around us has been upgraded and improved," according to Geigner.

"This is not a clear-minded, simple plan," said Polyzoides. "It's about EIRs, obstructions, and nonsense."

"The absence of a great planning document bespeaks the fact that there isn't a discussion going on," said Polyzoides, who added that "second-rate towns" are adopting the sort of plans that Westwood needs. (Despite repeated solicitation, representatives of the L.A. Planning Department were not available for comment.)

Isn't there a college around here?

At the same time, attempts to unite the Village under a marketing plan and leasing strategy have met with disaster. Several years ago, an attempted business improvement district "was badly managed," according to UCLA's Shoup, and became "one of the few BIDs in the country that's ever been disbanded." And despite its heft, UCLA traditionally stays out of land-use issues beyond its campus.

"I think it takes a concerted effort with the city, the local resident population, and the commercial property owners," said Gienger. "It's been very hard to get everyone on the same page."

A purposeful discussion may not arrive until 2012, when the specific plan is scheduled to be updated. In the meantime, the Village continues to surrender to nondescript eateries, beauty supply stores, and undistinguished chains. There is little discussion about the potential economic gain of student traffic. The Village has two student-oriented bars for the 36,000 undergrads and graduate students who study within walking distance.

Homeowner Brown said, "The bars certainly are in excess." Yet among many students, the Village's quietude is a running joke.

"Westwood's offerings are sub-par, to put it extremely diplomatically," said Sierus Erdelyi, president of the UCLA Law Student Association. "This does not make economic sense for what could be a bustling college town."

Other districts, such as downtown L.A. and Hollywood, are welcoming bars and clubs with bright new plans and outspoken boosters. In the Village, however, bars must primarily serve food and are therefore subject not only to liquor laws but also to the specific plan's limits on restaurant density. Nightspots cannot allow dancing, and the community often objects to such amusements as billiards and happy hours.

But in the effort to interpret the specific plan's elusive "balanced mix," Rose, the student body president, admitted that "apathy usually reigns off campus" and that students rarely assert their concerns in public processes.

This isn't to say that, there aren't bright spots in the Village for residents and students alike. Ralph's established a welcomed grocery store in the shell of a former department store, and Whole Foods followed soon thereafter. The Gap has left, but Urban Outfitters persists, and Trader Joe's is moving into the ground floor of the Palazzo. Hollywood premiers take place at the Village Theater, and hookah bars have thrived absent competition from alcohol.

And yet, just as the Palazzo's floors were being polished, the National Theater, a remarkable brown single-screen blob from the 1970s, met with a wrecking crew. A single story of retail, crowned by rooftop parking, will replace it.

Contacts & Resources:

Los Angeles Councilmember Jack Weiss, (213) 473-7005

Stefanos Polyzoides, Moule & Polyzoides, (626) 844-2400

Paul Geigner, Topa Management, (310) 203-9199

Westwood Village specific plan: http://cityplanning.lacity.org/complan/specplan/sparea/wwdvillagepage.htm

Palazzo website: www.palazzowestwood.com/home.htm