Environmentalists, open space advocates, planners, elected officials and residents of several Los Angeles and Orange County communities are gearing up for the next round in the battle over the fate of thousands of acres in the hills along the 57 freeway. The property owner has proposed developing 3,600 housing units and 300,000 square feet of commercial space, but opponents say most or all of the site should remain open as a wildlife corridor linking the Puente Hills Open Space with Chino Hills State Park.

Interestingly, the corridor was not included in a large report on "missing linkages" issued in mid-March by the group South Coast Wildlands in conjunction with numerous government agencies (see sidebar). One report author said the corridor is indeed a linkage, but it is not one of the 15 top Southern California priorities.

Still, those with concerns about development in the hills are unlikely to be deterred as the City of Diamond Bar moves forward with processing a master plan for Aera Energy's 2,935-acre site.

"The project involves grading two-thirds of the entire property," said Bob Henderson, a Whittier city councilman and chairman of the multi-agency Wildlife Corridor Conservation Authority. "When you think about that, it's devastating from a biology point of view."

But Diamond Bar City Manager James DeStefano insisted that it is too early in the process for anyone to draw conclusions. "There are a lot of issues out there we are still examining," said DeStefano, who estimated a draft environmental impact report is "months" from completion.

Yet the project is hardly new, and neither is development of the land. Shell Oil began punching oil wells into the hills during the 1920s, and the property was both a productive oil field and cattle grazing land for decades. With oil about played out, Aera Energy, a joint venture of Shell Oil and Exxon/Mobile that produces 30% of California's oil and gas, first proposed its development to Los Angeles County. All but about 320 acres of the site lie in unincorporated Los Angeles County; the remainder is in unincorporated Orange County.

Los Angeles County planners conducted their first meeting on the project in 2002, said Paul McCarthy, a supervising regional planner for the county. Most of the site is within a "sensitive ecological area" designated by the county general plan, so planners and biologists raised a number of questions. The county's Significant Ecological Technical Advisory Committee eventually asked Aera to redesign the project to lessen the impact on wildlife connectivity. Instead, Aera took its proposal to the City of Diamond Bar, which approved a planning and pre-annexation agreement with Aera in late 2006.

In May 2007, the city issued a notice of preparation for a program environmental impact report and conducted a scoping meeting. City officials initially said a draft of the environmental study would be complete before year's end, a timeline that has slipped.

"There was a lot back in that day we didn't really know," conceded DeStefano. "We have been going slowly through the project. There has been information that has taken a lot of time to get to us."

Aera is working with The Planning Center on the master plan and environmental study, while the city has retained EDAW to review Aera's submittals. DeStefano said the city has no pre-conceived notions. "We are taking a real hard look at the land planning that is being proposed by the developer," he said. "We don't want this to be just another subdivision on a hillside. We want it to be a model."

The latest public proposal is for a master plan divided among three jurisdictions.

• Diamond Bar: 1,940 acres containing up to 2,800 residential units, at least 100,000 to 200,000 square feet of commercial development, and a 20-acre sports park. Diamond Bar would have to annex all of this territory, nearly all of which is outside its existing sphere of influence.

• Los Angeles County: 675 acres containing 275 housing units and a golf course.

• Orange County: 321 acres with a maximum of 800 residential units, 100,000 square feet of office or commercial space in mixed-use developments, and a golf course.

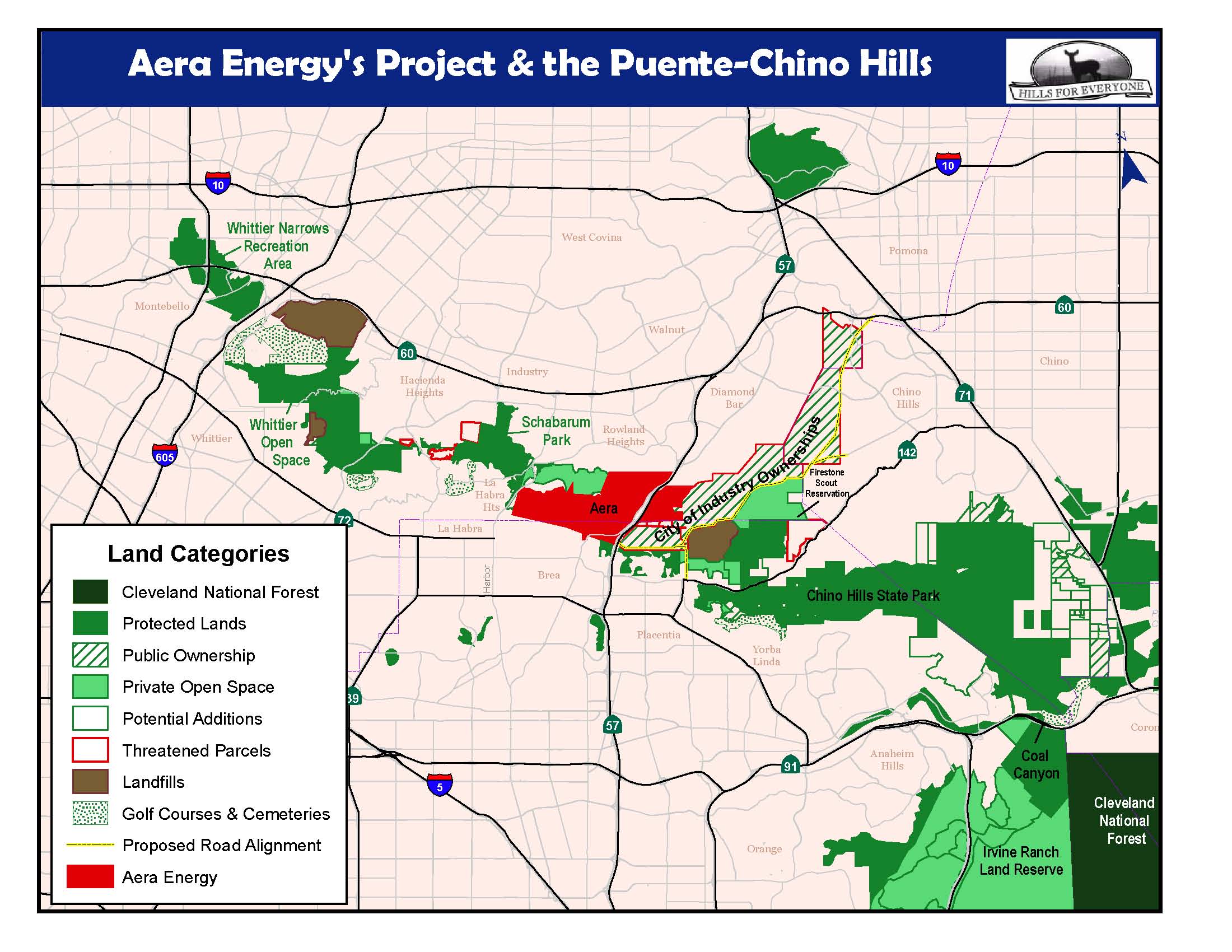

Environmentalists say the Aera project site is located in a critical wildlife habitat corridor. Map source: Hills For Everyone.

At least half of the nearly 3,000-acre site would be designated as open space, although golf courses would be part of the open space. Aera has defended the proposal as providing needed housing in a region that has few large sites available for development, yet compatible with environmental needs.

"The project was designed to incorporate a wildlife movement corridor through the property from the earliest stages of planning," according to Aera's project description. "Recognizing that animals can safely cross under Harbor Boulevard and the SR-57 freeway in only one location on each road, the plan's design sets aside about 700 acres (of the project's 1,670 acres of preserved open space) to allow unimpeded passage between these locations that lead to adjacent open space preserves."

DeStefano said his city has not had a lot of contact with other cities about the project. Back when Los Angeles County was processing Aera's application, the cities of Whittier, Brea, La Habra and La Habra Heights all adopted resolutions opposing the project. The Roland Heights Community Coordinating Council in unincorporated Los Angeles County is also an opponent. The surrounding jurisdictions are concerned about traffic, loss of scenic views, and impacts on wildlife. They are also concerned about their past investments in open space, as local governments have worked with state agencies to conserve about 40,000 acres stretching from the San Gabriel River to the Cleveland National Forest during the last two decades.

The Aera property is located toward the western edge of this open space, between the 4,000-acre Puente Hills Open Space (between Whittier and La Habra Heights) and the 12,400-acre Chino Hills State Park, which connects via open space in Coal Canyon to Cleveland National Forest. The Aera property is crucial for healthy movement by deer, foxes, bobcats, coyotes, opossums and other animals, according to open space advocates. The property contains oak and walnut woodlands, as well as coastal sage scrub habitat important to rare species of birds.

Aera has portrayed the property as highly degraded by oil drilling and more than a century of cattle grazing, but open space advocates are not dissuaded. About 900 acres the wildlife authority purchased from Chevron in 1995 was in far worse condition than Aera's property is, but the Chevron property has rebounded quickly, Henderson said.

One concern of Henderson's is the amount of grading proposed. The EIR notice of preparation estimated there would be 57 million cubic yards of cut and fill work over two-thirds of the project site. Henderson finds that level of earthmoving unacceptable.

Henderson and others, including the influential group Hills for Everyone, would like for Aera to sell the property to a public entity for preservation. Henderson added, though, "I've never been opposed to cutting down the size of the project drastically and making room for the wildlife corridor."

Whether that's feasible is unknown. Los Angeles County's McCarthy said that Aera and Diamond Bar "have a real challenge on their hands as to how they mitigate impacts to the biotic habitat that's there."

For the most part, environmentalists and surrounding jurisdictions are simply waiting for release of the draft EIR. "Until we see an EIR out of the City of Diamond Bar, we're sort of in a holding pattern," said David Sommers, a spokesman for Los Angeles County Supervisor Don Knabe, who represents the area. "We want to make sure that Diamond Bar is not just picking and choosing the best parts of the site."

Possibly complicating the habitat issue is the City of Industry's purchase in 2001 of 2,500 acres in Tonner Canyon, just to the east of the Aera property and adjacent to about 3,000 acres Industry already owned in the hills (see CP&DR Local Watch, December 2001). The wildlife authority and other entities sued over the 2001 acquisition but lost in court. Industry — which is home to 700 residents and nearly 100,000 workers — has talked about building several reservoirs on the site, but no project has emerged. The concern is that large reservoirs could eliminate thousands of acres of habitat and block wildlife movement.

Contacts:

Jim DeStefano, City of Diamond Bar, (909) 839-7010.

Bob Henderson, Wildlife Corridor Conservation Authority, Whittier City Council, (562) 945-8200.

Paul McCarthy, Los Angeles County Department of Regional Planning, (213) 974-6461.

Aera project website: http://www.aeracommunity.com/

Hillside Open Space Education Coalition: www.hosec.com

Hills For Everyone: www.hillsforeveryone.org

Report Identifies South State Wildlife Linkages

Billed as an "innovating conservation strategy" by environmental groups and public agencies, the "South Coast Missing Linkages Project" advocates conservation of 15 key corridors stretching from the southern Sierra Nevada Mountains to Baja California.

The project aims to conserve the existing connections that biologists say are essential. The connections lie between large chunks of national forest, state parks and other public open space.

"If even one fails, the biological integrity of the entire region would be compromised," said Kristeen Penrod, conservation director for the group South Coast Wildlands. "If these 15 linkages were conserved, they would form the backbone of the Southern California ecoregion." Others involved in the project include the National Park Service, the U.S. Forest Service, California Department of Parks and Recreation, The Wildlands Conservancy and The Nature Conservancy.

"Without linkages between existing parks, national forests and other public lands, many native species could be threatened or disappear entirely," said Ray Sauvajot, chief of planning, science and resource management for the National Park Service in the Santa Monica Mountains. "This is especially true for animals that disperse widely or have small populations, such as mountain lions, badgers, bobcats, desert tortoises and bighorn sheep."

The strategy evolved out of a project back in 2000 that identified 232 linkages statewide, including 69 in the south coast "ecoregion." Recognizing that they could not address all of the linkages, the participants decided to prioritize the top 15 Southern California linkages based on their vulnerability to urban development and their "ecological irreplaceability," Penrod explained. The park service and other government agencies provided a great deal of information on species and habitats for the report.

The priority linkages are all 1,000 acres or more and feature both high-quality habitat and multiple habitat types, Penrod said. About half are already public lands or are preserved in some fashion. Many of the linkages also are already included in habitat conservation plans or natural communities conservation plans. Purchase, easements, zoning restrictions and mitigation agreements are all potential ways to ensure the corridors' viability, according to Penrod.

The report is a useful tool for the park service as it looks to acquire new territory for the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, and as the agency reviews local general plans in the area, said Sauvajot.

Several local agencies, including Ventura, Los Angeles and San Diego counties and the City of Santa Clarita have already shown interest in using the linkages project for long-range planning.

The full report and detailed maps are available on the South Coast Wildlands website, www.scwildlands.org