The Salton Sea sits likes a time bomb in the desert, serving up a brew of bad smells, turgid waters and the potential to increase air pollution in an area where thousands of homes are planned. But under a proposal making its way through the Legislature, some of the sea's lurking hazards may be stopped. Instead, the Salton Sea may be shrunk to a third of its current 240,000 acres and revived as a recreational lake for sport fish and migrating birds. All it will take is billions of dollars and at least 75 years of maintenance.

The sea, created accidentally from an overflowing diversion of Colorado River water 100 years ago, is Southern California's largest body of water. But for the past half century, it has been dying as its water supplies have been cut off and channeled to agriculture and growing cities. The lake will be officially considered dead by 2017, after about 300,000 acre-feet of agricultural runoff that now flows into the sea will be diverted instead to San Diego.

This is not the first plan to save the lake, but the plan maybe the final hope. The state Resources Agency in May released a programmatic environmental impact report that has been embraced by stakeholders in the region. Before the end of the legislative year in September, action is expected on a bill, SB 187 (Ducheny), that would approve the plan, provide initial money and chart future steps. The cost � as much as $8.9 billion over 75 years, including millions of dollars a year for maintenance � may prove the most daunting part of the restoration. Only about $200 million will be available if the Legislature acts this session, leaving future outlays to be provided by money from a proposed redevelopment district, federal funding and future state bond measures.

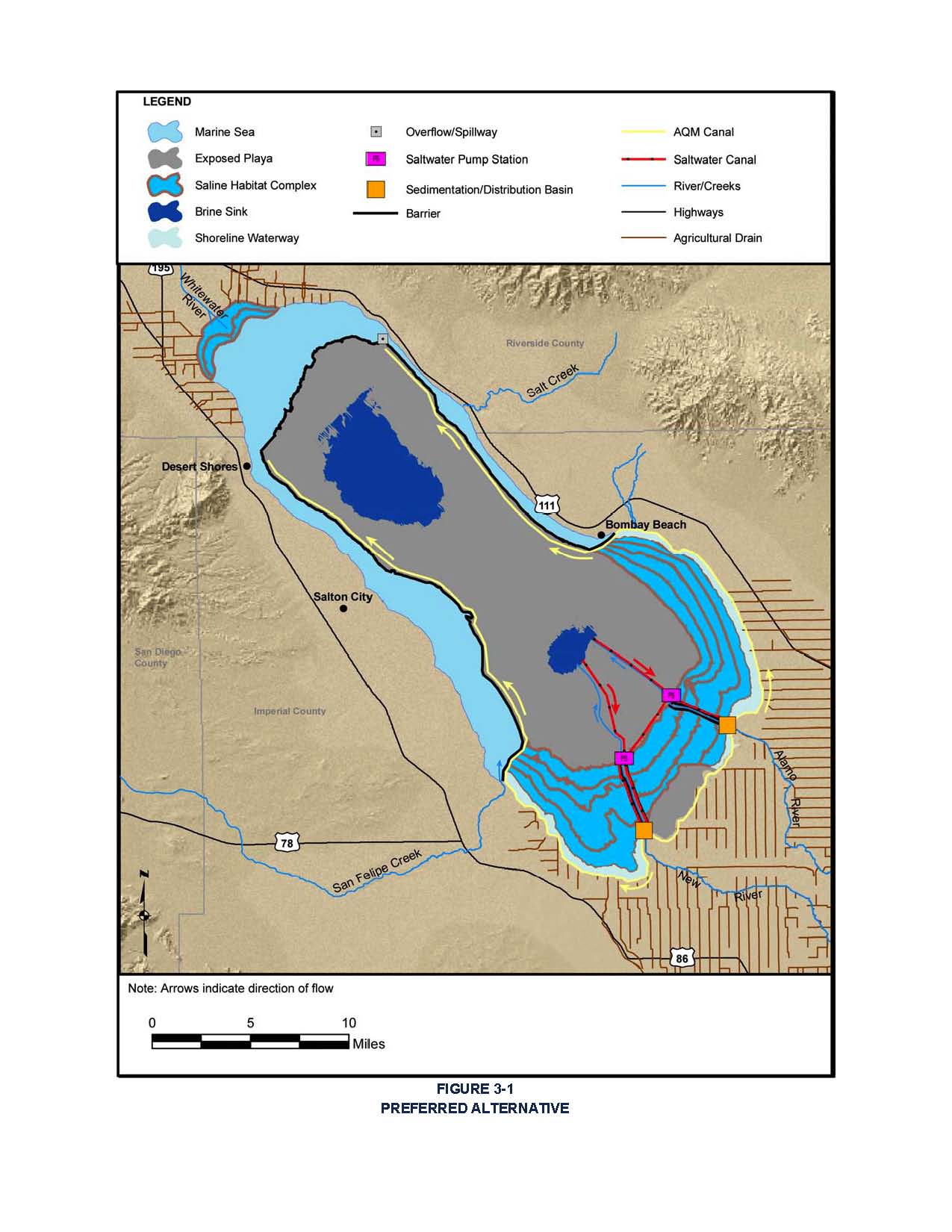

The EIR proposes cutting the existing 376-square-mile sea into a horseshoe shaped waterway with a 52- mile-long rock jetty. The jetty would be hugely expensive, costing an estimated $5.7 billion to construct. The northern portion of the lake would be reinvigorated primarily as a recreational lake with fish, while the southern half would be dried out in portions, ringed by a watery shoreline of smaller ponds for fish, plants and migrating birds. The southern half would include 64,000 acres of wetlands that would be stocked with small fish and worms on which birds feed.

Cutting the lake in two and, therefore, having a much smaller area to replenish is one aspect of improving the water quality. The primary cause of poor water quality, however, is phosphorus from untreated agricultural runoff, according to Rick Daniels, executive director of the Salton Sea Authority, a local joint-use authority. A project-specific EIR is expected to address how the runoff would be treated.

Work needs to be partially completed on the most critical areas by 2017, when runoff from Imperial County farmers that now flows into the lake will decrease because irrigation water will be transferred to San Diego, under terms of a 2003 agreement on the Colorado River among several water agencies (see CP&DR Legal Digest, August 2007; CP&DR, November 2003).

"The sea is on its way to dying," Daniels summed up.

The sea is dying as it grows more salty and its freshwater sources are cut back. The sea has 44 parts of salt per 1000 today, compared with 43 parts per 1000 in 1999, according to Daniels. In contrast, the Pacific Ocean's salinity is 35 parts per 1000. (See CP&DR Environment Watch, February 2000).

That saltiness makes it hard for fish to survive. Eight years ago, for example, the sea was home to such fish as croaker and a sport fish named the corvine. But those fish, Daniels said, stopped reproducing. Today, only the hardy tilapia remains, and it too faces problems. Tilapia came to the sea after being added to nearby irrigation canals to eat vegetation growing there, and it adapted to the saltwater of the Salton Sea, he said. Today there are 200 million tilapia in the sea, but three million a year are dying off due to the increased growth of algae, which is fed by phosphorus in agricultural runoff from the Imperial Valley.

And things could get worse. Under the state's preferred alternative in the EIR, a total of 62,000 acres of sea will be dried out, potentially creating more dust and decreasing air quality in the region. Daniels noted that dried up lakes in the Owens Valley have led to huge dust storms that make Owens Valley one of the most polluted air basins in the country. "We're afraid it's going to be worse" in the Salton Sea area, he said,

The dried up land is called "exposed playa" in the state's EIR, but it's no day at the beach for future recreationists. The land will be off limits to the public, and it will be planted with salt tolerant vegetation and covered with gravel. The state plan anticipates that dust mitigation will be an ongoing expense.

According to Dale Hoffman-Floerke, chief of the Colorado River/Salton Sea office of the California Department of Water Resources, a crust will form on the surface after the water evaporates, minimizing the dust. She disagreed with Daniels' contention that the state proposal will harm air quality.

"Our goal is to insure that air quality is not made worse as the result of any restoration activity," she said.

Daniels said the Salton Sea Authority continues to work with the state on its plan, but the authority has developed another plan that does not require as much of the sea to be dried up.

Meanwhile, development continues in the region. More than 800 homes were built in Salton City, in unincorporated Imperial County, in the past two years alone, Daniels said, and other developers are waiting to start building thousands of approved housing units just north of the lake in Riverside County. Some may wait to see what the future holds for the lake before they begin building.

"My belief is, as this progresses, there will be many more houses built there, as the water improves," Daniels said.

Money for initial work on the sea is expected to come from $30 million in federal funding, along with $47 million from Proposition 84 bond funds approved by voters in 2006. Those funds will be used to restore and upgrade habitat along the New and Alamo rivers, which drain into the sea from the south in Imperial County. Also, as part of 2003 settlement on Colorado River water, Coachella Valley, San Diego and Imperial Irrigation Districts put $40 million each in a mitigation fund for the Salton Sea.

Another $1 billion might come from a $10 billion water bond that State Senate President Pro Tem Don Perata has proposed. Daniels said there is also talk of creating a redevelopment district around the lake to raise another $1 billion. The Legislature authorized creation of the district in 2000. The redevelopment plan would capture increases in property taxes as land values begin to rise due to improvements to the sea, Daniels said.

State officials are also expected to ask Congress to allocate another $1 billion next year, he said.

Environmental groups, so far, are in favor of the state's EIR. "It's not perfect," said Kim Delfino, California director of Defenders of Wildlife, which represents a coalition of environmental groups including the Sierra Club and the Audubon Society through an organization called the Salton Sea Coalition. But the plan, she notes, does have the basic elements the groups are seeking: habitat for wildlife, and protection of air and water quality.

Delfino and Hoffman-Floerke both said a key issue awaiting resolution is who will become the governing body for the sea's restoration. The organization will need to involve state, local and federal officials.

Delfino said she is researching whether a partnership being used by state and federal governments to restore Florida's Everglades may be a good model for the sea. But, like Daniels, she said something must be done to restore the sea � and soon.

"We're running out of time," she said.

Contacts:

Rick Daniels, Executive Director, Salton Sea Authority, (760) 564-488.

Kim Delfino, Defenders of Wildlife, (916)313-5800, ext. 109.

Dale Hoffman-Floerke, Department of Water Resources, (916) 651-7052.

Salton Sea EIR: http://www.saltonsea.water.ca.gov