This article is provided to you for free by the paying subscribers to California Planning & Development Report. To learn how you too can subscribe to CP&DR and support our work, just click here.

A few weeks ago, Nevada Governor Joe Lombardo ran an unusually whiny guest essay in the New York Times. He complained about inflation, interest rates, and increases in housing prices. Most of all, he complained about land use.

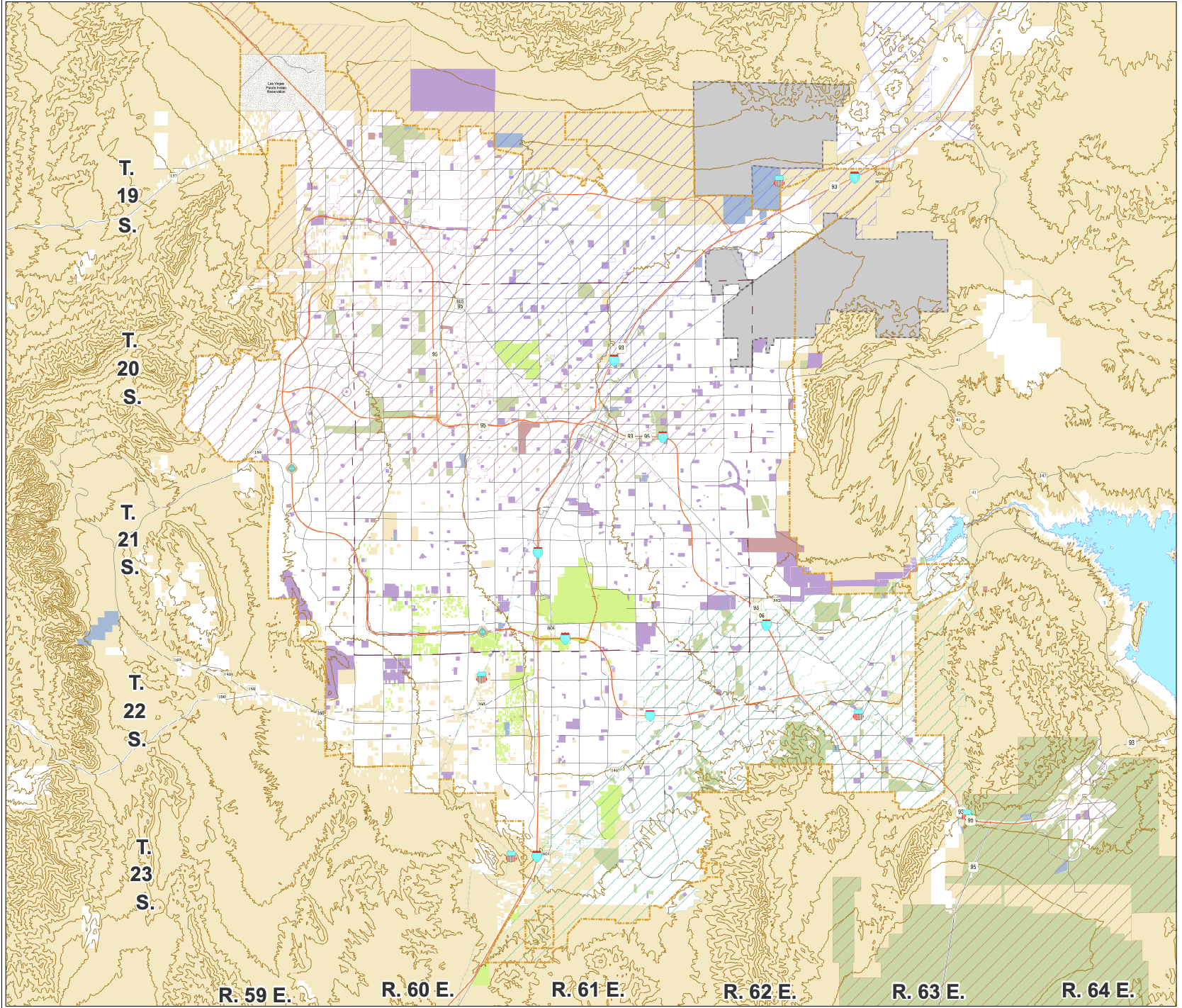

The federal government controls 80% of the land in Nevada, mostly through the Bureau of Land Management. Lombardo cited estimates that, at the current pace of development, the Las Vegas metro area will run out of developable land as early as 2032. "The reality of this ownership surrounding the urban areas of the state is a limiting factor on the development of new housing options," he wrote. (I'm sure water supply is another factor, though he didn't mention it.)

He has a point: the Las Vegas Review-Journal has declared a "housing crisis," with home prices up to an average around $450,000 and a shortage of 78,000 affordable rental units. Otherwise, this is nothing new in Nevada politics.

Until the Golden Knights arrived, complaining about the Bureau of Land Management had long been the state's most popular sport. Lombardo's request was, though, more specific than the general libertarian griping that Nevadans are used to. He called for the Biden administration to open 50,000 acres of desert to development so Nevada can add as many as 335,000 homes for anyone who enjoys their American Dream cooked medium rare.

It's worthwhile for us Californians to keep tabs on our neighbors to the east. We have an alpine lake to care for, interstate highway traffic to manage, supertrains to develop, tortoises and Joshua trees to protect, and athletic teams to plunder. And, a concerning, but understandable, percentage of mostly middle-income Californians have considered decamping for Nevada.

Those folks are exactly who Gov. Lombardo would like to settle on whatever land he can wrest away from the feds. (His essay doesn’t mention it, but it alludes to a bill introduced by Utah Rep. John Curtis to facilitate the sale of federal land nationwide.)

A few decades ago, the idea that Las Vegas might run out of land would have been laughable. In 1980, the metro area's population was 438,000 (about the size of Reno's today); now, it's almost 3 million.

The situation Las Vegas faces today is a version of the one that most of California's major urban areas faced decades ago: constraints to growth. San Francisco has been hemmed in since the Victorian Era, and Oakland has always been squished between mountains and bay. In Los Angeles, "sprawl hit the wall" in the 1980s. Even the Inland Empire cannot gallop as it once did. In each case, mountains, coastlines, other cities, and, yes, protected open spaces have forced cities to grow through density rather than expansion.

The problem in California to accommodate more people has not generally equated with an embrace of density. The densification of California has been built on awkward constructions like the dingbat, the strip mall, and, more recently, five-over-one apartment buildings. Much of our dense development has taken place on commercial corridors, which, though nominally efficient, are inherently ugly. The most pleasant neighborhoods, where skilled architects could likely work wonders on attractive, appropriate designs, are often those that are most reluctant to grow. We have, so far, failed to create graciously dense places, and instead settle for too many self-defeating jumbles that give density a bad name.

At 5,046 residents per square mile, the City of Las Vegas is not exactly Hoboken, but it’s denser than you'd imagine (compare with Phoenix, at 3,100). It has plenty of small houses on small lots (making it relatively inexpensive on a per-unit basis), and it has its share of small apartment buildings. Many residents commute to one of the greatest concentrations of employment (especially blue-collar employment) in the country: the Las Vegas Strip. So, there are gravitational forces keeping residents in the city.

And yet, it's a fraction of the density of some of the cities celebrated by its hotel-casinos. More importantly, it wears its density awkwardly -- far more so than most major California cities. The City of Las Vegas has a Walkscore of 42 (meaning "car-dependent," which seems generous). Walkability plummets to 33 in North Las Vegas, and 30 in Henderson. By contrast, the City of Los Angeles scores 69.

Lombardo’s proposal would accomplish two things: 1) promote low-density sprawl; and 2) undermine the city’s incentives for (denser) redevelopment.

To its credit, Las Vegas wants to grow. It wants none of the slow-growth paralysis that has hobbled too many parts of California. Unfortunately, Lombardo's plea indicates that he wants Las Vegas to continue to sprawl, presumably by continuing to build inexpensive single-family homes, parking-heavy apartment complexes, and whatever inconsequential commercial developments are needed to keep suburbanites fed, fit, and fueled up.

We all know how that is going to end. Even the Nevada desert is not infinite. In the meantime, even Las Vegans don't want hourlong commutes. Even a place accustomed to extreme heat probably doesn't want climate change to get worse.

"Nevadans know what hard work looks like," Lombardo writes. If that's the case, he and his constituents should be all about density. Density is hard work. Urban design is hard work. Sustainability is hard work. Walkability is hard work. Favoring greenfield development is taking the easy way out.

Lombardo has said that provision of housing "begins with eliminating governmental barriers to development." Sure, but it doesn't have to be the federal government that does the eliminating.

He could instead do what his California counterparts Govs. Brown and Newsom (along with legislators) have been doing for the past decade. He could instead focus on local governments and their development policies. He could collaborate with planners and developers. They, and other stakeholders, could reach a consensus about what a denser Las Vegas could be like. They could encourage innovative design rather than the same old expedient stucco boxes that is advertised as "resort living" that populate inland California communities from Victorville to Hemet to Santa Clarita. They could build genuine urban neighborhoods, worthy of Las Vegas's global reputation, rather than what is essentially a forgettable back-of-house to serve the Strip.

Back in 1972, architects Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steve Izenour famously celebrated Las Vegas’s design sensibilities. They reveled in the superficiality of signage and simulacra. Now, Las Vegas--not the Strip, but the actual city--faces the opportunity to get real.

It could be more dense. It could be more efficient. It could be both inexpensive and attractive. It could take a cue from all the ersatz historicism that it's famous for, accept the gift of artificial constraints, and consider a new approach to urbanism. Granted, Las Vegas is probably never going to be Paris, Venice, or New York. It could, though, be cosmopolitan. Or it could be Riverside.

In short, with a little imagination--real imagination, not just spectacle--southern Nevada could learn from the lessons that California so vividly teaches.

Don't get me wrong. Water supply notwithstanding, I don't want Las Vegas to not grow. If done right, a denser Las Vegas will accommodate California exiles and anyone else who wants to live there -- it'll just do it better than it currently does. And California needs a little competition. Let's compete for residents and let the best state -- not the luckiest one, or the whiniest one--win.

Map courtesy of Bureau of Land Management. Image courtesy of Andrew via Flickr.