California has suffered plenty of perverse effects of Proposition 13: cuts to school funding, ossification of neighborhoods, general constraints on cities, etc. Most of those effects are by design or were, at least, foreseeable by Howard Jarvis and the measure’s supporters.

In Los Angeles County a new unintended consequence has arisen that, though it might prove great for the county, probably has Jarvis spinning in his grave.

This week, Measure M officially made it on to the countywide ballot for November. The successor to 2008’s Measure R, Measure M would further the region’s long-range transportation plan by augmenting and extending the county’s half-cent sales tax indefinitely (30-plus years at least) to generate tens of billions of dollars for transportation projects.

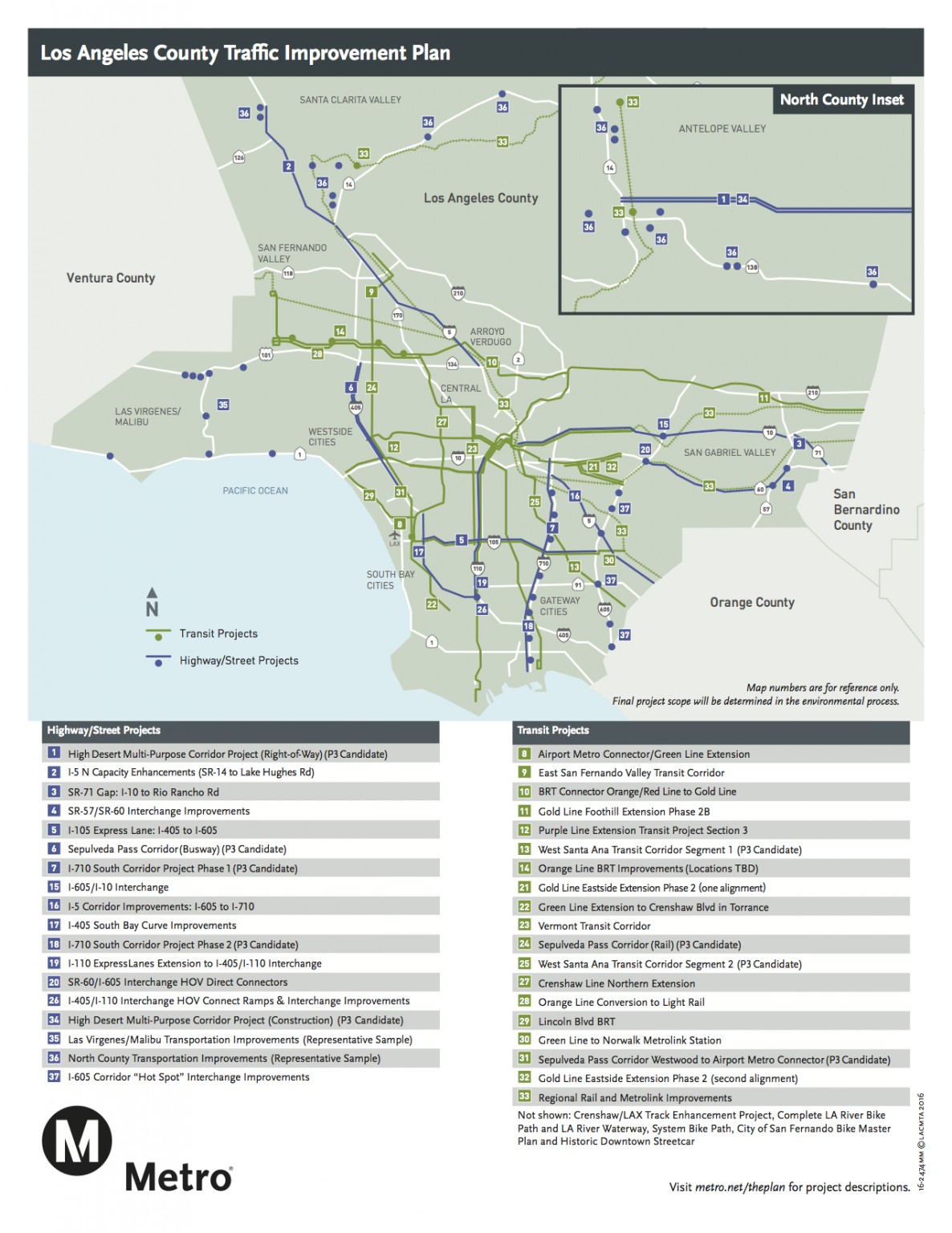

Like Measure R, which paid for popular projects like the Expo Line to Santa Monica and Gold Line extension to Azusa, Measure M is a Christmas tree of projects, sprinkled around the county so that the measure will appeal to just enough voters to make it pass. And, at an estimated $800 million in annual revenue, Measure M is one big Christmas tree — Rockefeller Center big. It includes 27 highway projects, 33 transit projects, and a good deal of local return monies. Many people are excited about these projects, and with good reason.

In some ways, though, the number of projects and amount of expected funding is a direct consequence of the number of voters that Measure M has to woo. That number is two-thirds of the electorate. That’s the margin needed to pass a new tax in California. Thanks to Proposition 13.

In some ways, though, the number of projects and amount of expected funding is a direct consequence of the number of voters that Measure M has to woo. That number is two-thirds of the electorate. That’s the margin needed to pass a new tax in California. Thanks to Proposition 13.

The Jarvis people thought that this provision would curb public spending and ease Californians’ tax burden. At the very least, they sought to ensure that proposed taxes were structured sensibly enough to appeal to a broad swath of voters. Measure M, though, is different.

The great thing about planning is that plans on paper cost nothing. Therefore, it costs Metro nothing — at least not up-front — to heap on project after project to appeal to different jurisdictions and different interests groups. Measure M has something for everyone: drivers, transit advocates, bike advocates; city people, valley people, South Bay people, even high desert people.

Metro’s hope is that if people don’t vote for the interests of the county as a whole, they’ll at least vote for their own parochial interests. That’s why even small jurisdictions and institutions — some as as specific and localized as Cal State University, Northridge — are keeping score. As the Los Angeles Daily News reports, not everyone is happy, especially cities in south and southwestern L.A. County. Metro just hopes that enough people are happy. (Note: Now that it's on the ballot, Metro cannot directly lobby for the measure.)

You could call it politicking, but Metro is doing nothing if not playing by the rules.

It’s not hard to imagine, though, that if the rules required a simple majority, the Measure R package would look much different. For starters, package that had to appeal to only 50 percent of voters would likely be smaller. It also might be more efficient. It might, for instance, omit a rail line from Torrance to West Hollywood or a highway to Palmdale, willfully sacrificing voter support in favor of projects that will be more cost-efficient and/or serve more people. It might be able to put more money into active transportation in the urban core and less money into highways serving the suburbs.

I'm not making value judgements about any of these projects. I'm just saying that Metro's strategy might have been different in a non-Prop 13 world.

In other words, Prop 13 compels Metro, and anyone else seeking to raise revenue via a vote, to come up with not necessarily the best spending program but rather the spending program that has the best chance of passing.

While we can be sure that many Prop 13 advocates will want nothing to do with Measure M, we can be equally sure that over the next few months transit advocates in Los Angeles will be crying “All aboard!” to rouse support for Measure M's proposed trains.

Or at least, “Two-thirds aboard!”

Image credit: L.A. Metro